In these rather unhappy days I chose pictures from the last week of March that made me feel happier. I hope you enjoy them! Joanne Doucette

This picture is of Charles Coxwell Small, the Family Compact member who owned all the land from Coxwell Avenue to Woodbine Avenue and from Ashbridge’s Bay to Danforth Avenue. He used a wheelchair because he was partially paralyzed as the result of a stroke. His workplace, the old courthouse on Adelaide Street east of Victoria Street, made itself accessible with ramps so that he could continue in his job. We’ve changed a lot as a society since the mid-nineteenth century and I’m glad of that too. As a person with a disability I need ramps and elevators and, basically, any place with stairs is off limits to me. The world is a happier place for inclusion, equality and diversity.

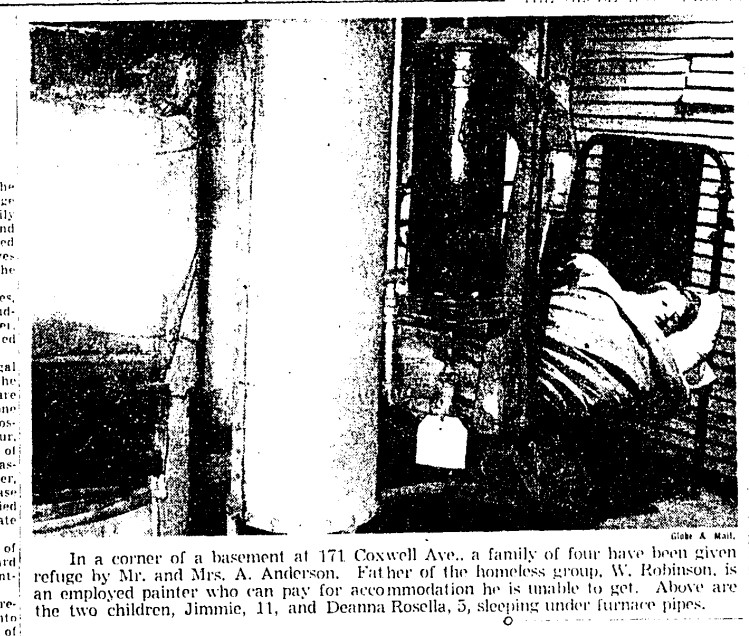

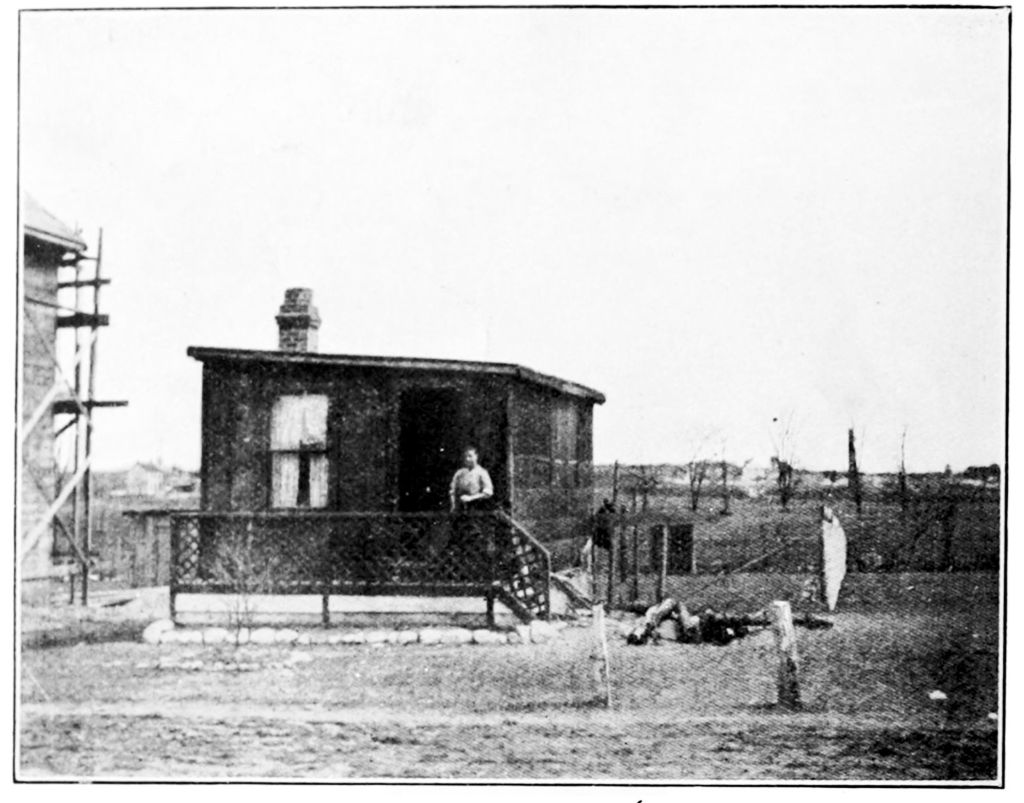

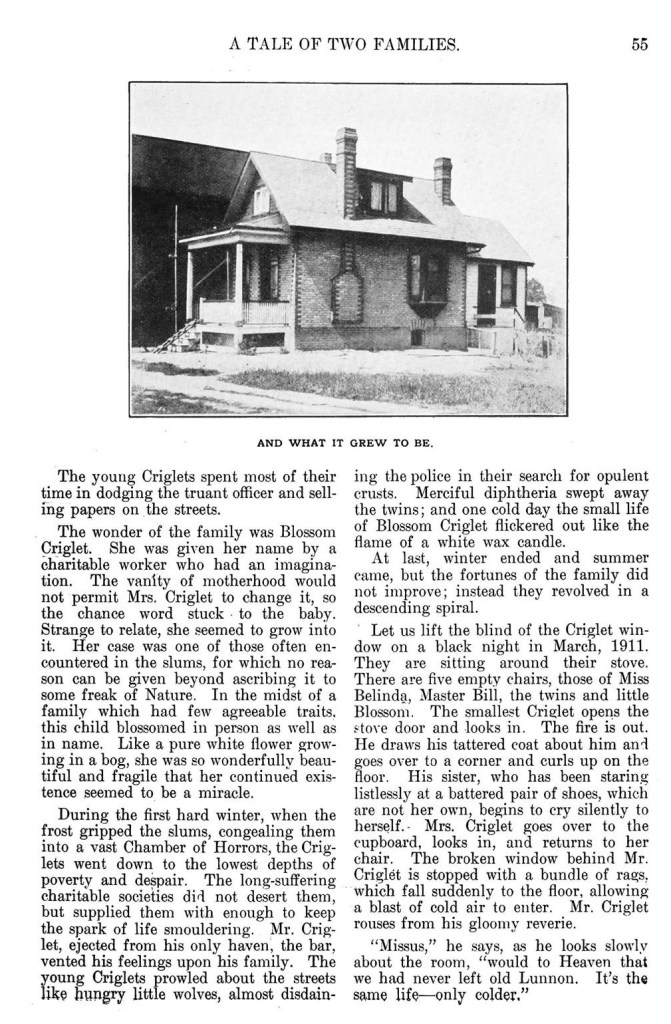

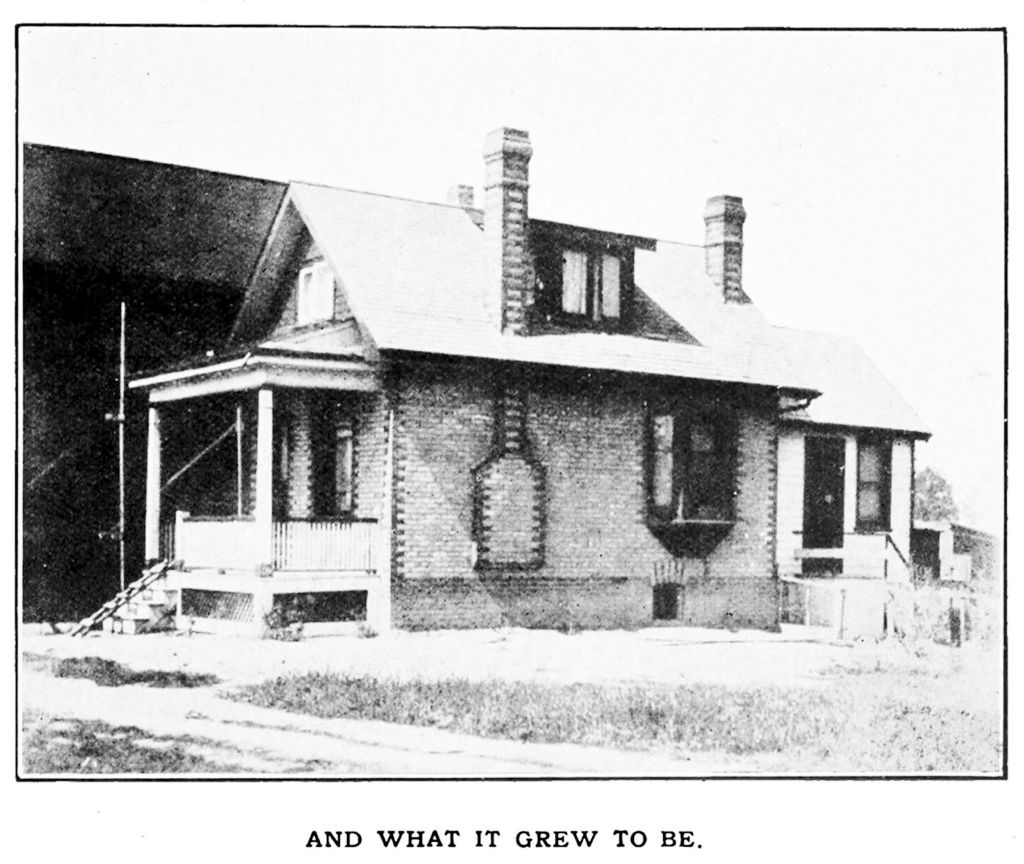

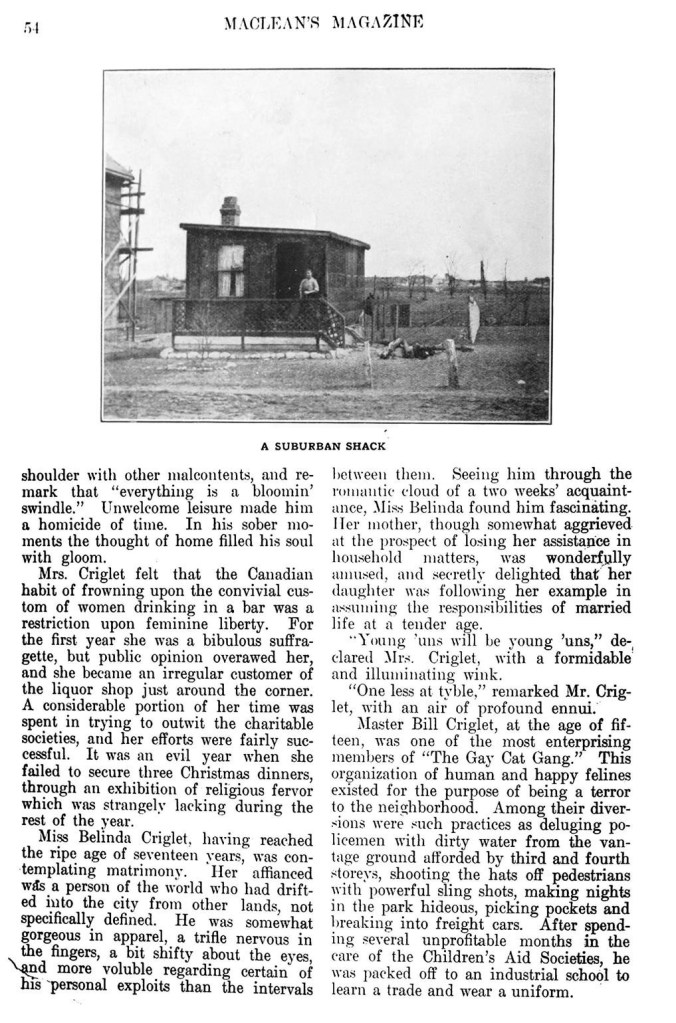

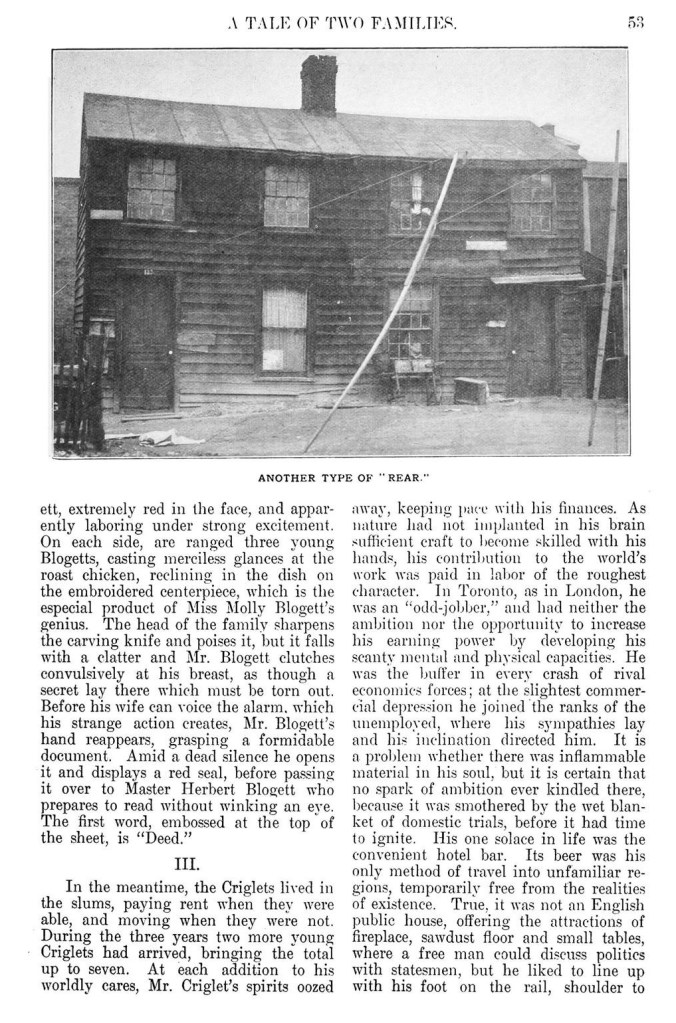

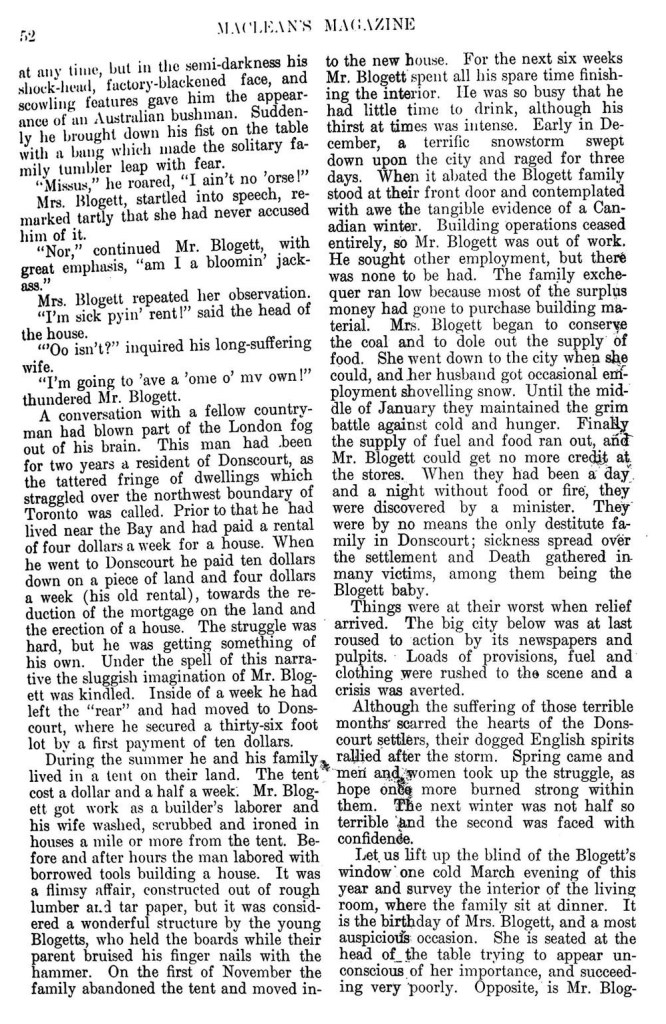

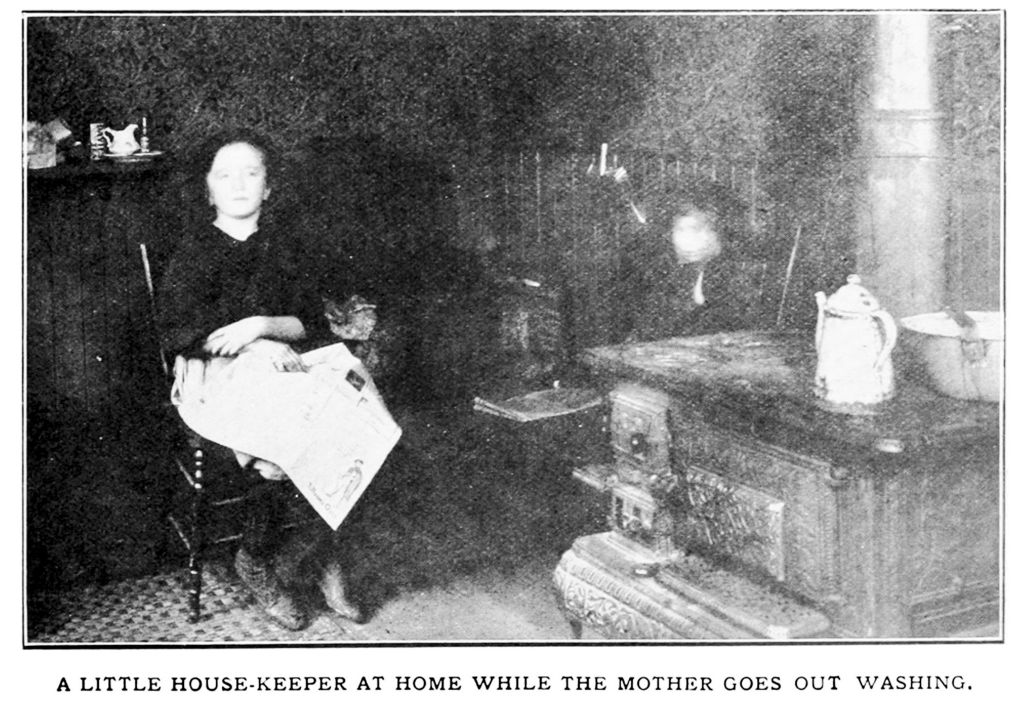

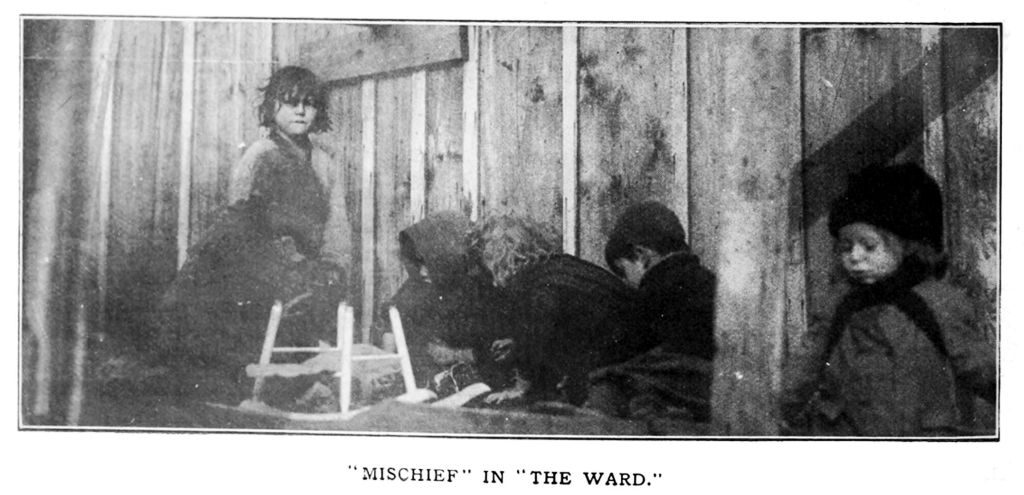

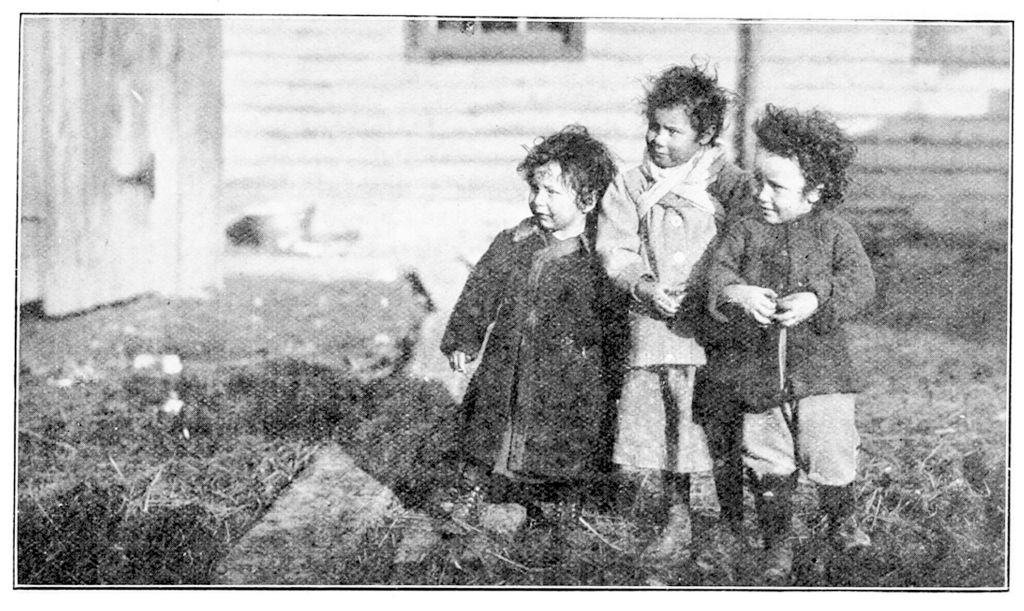

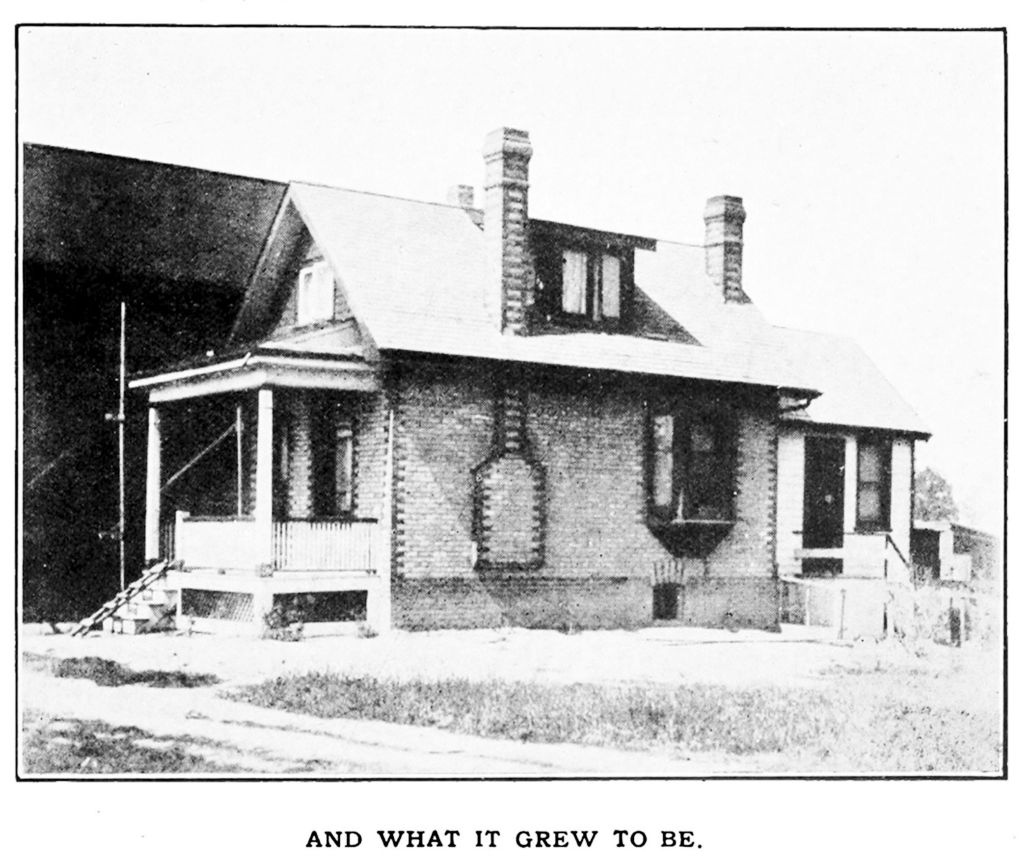

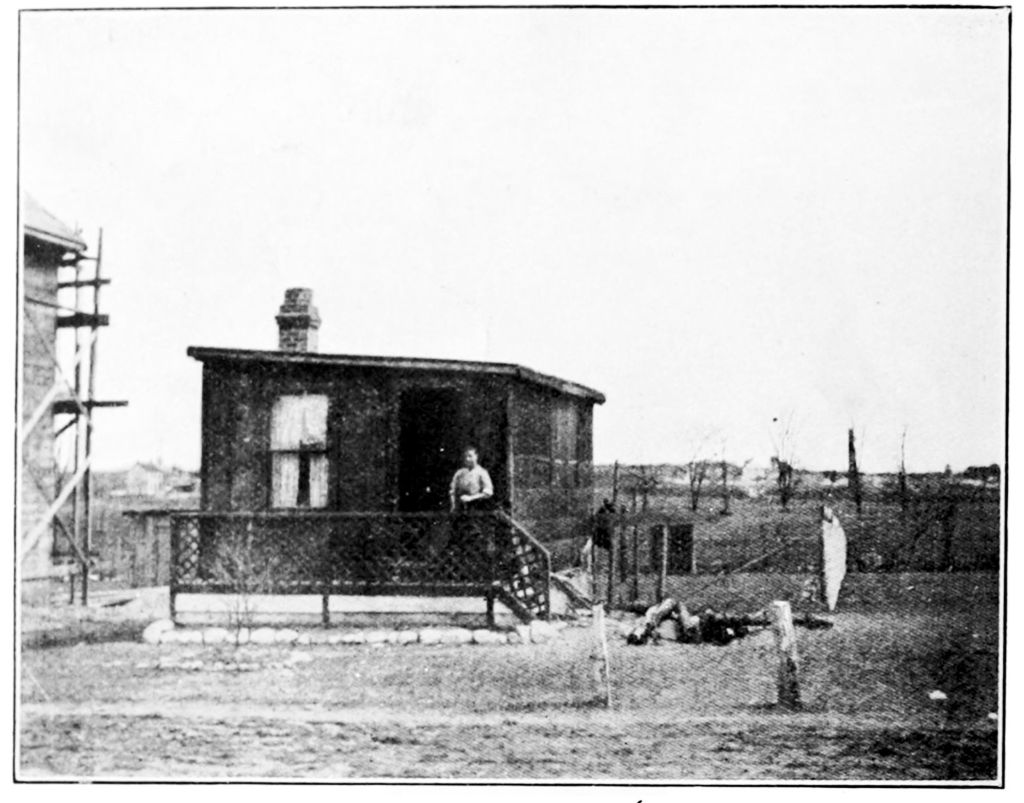

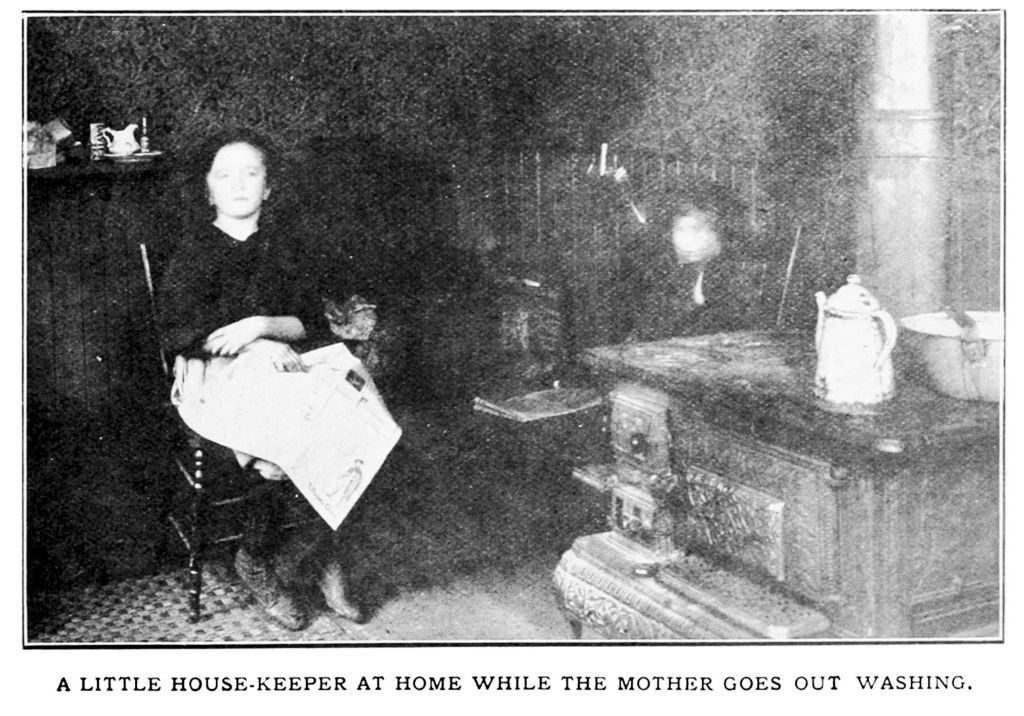

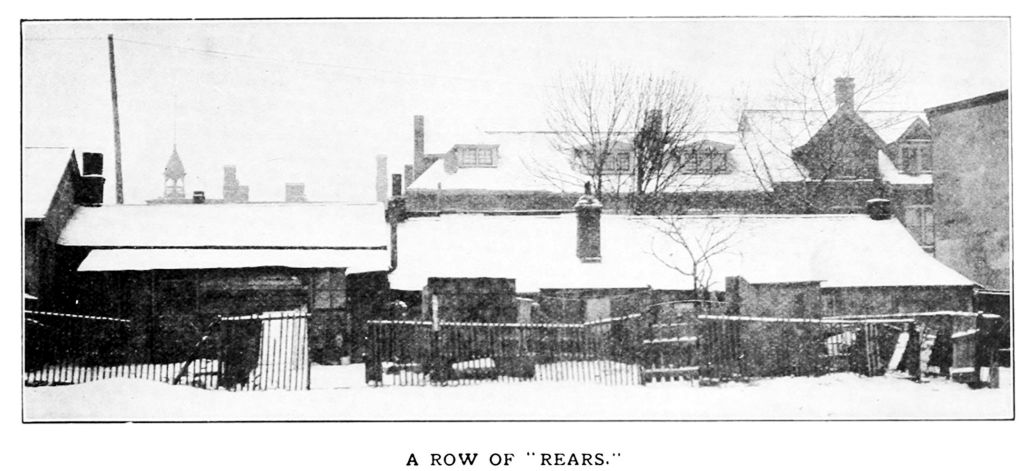

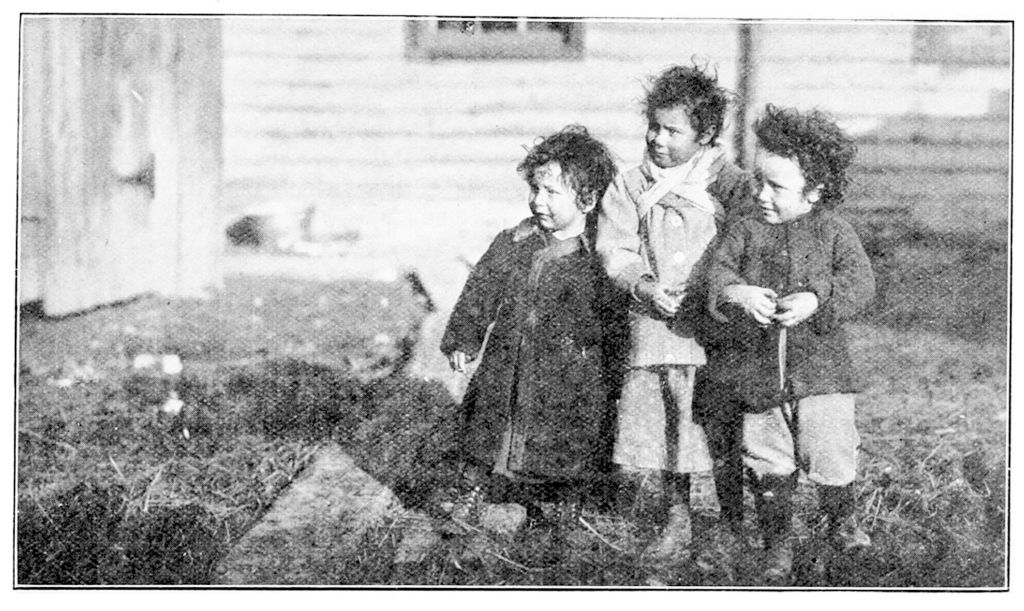

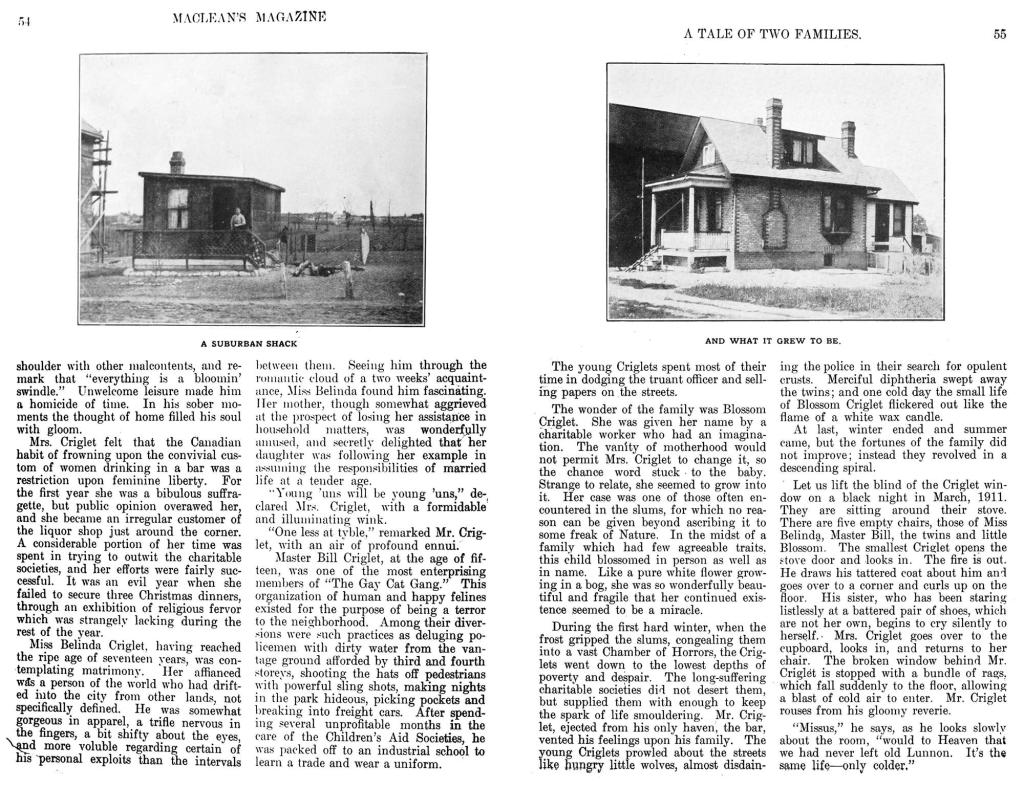

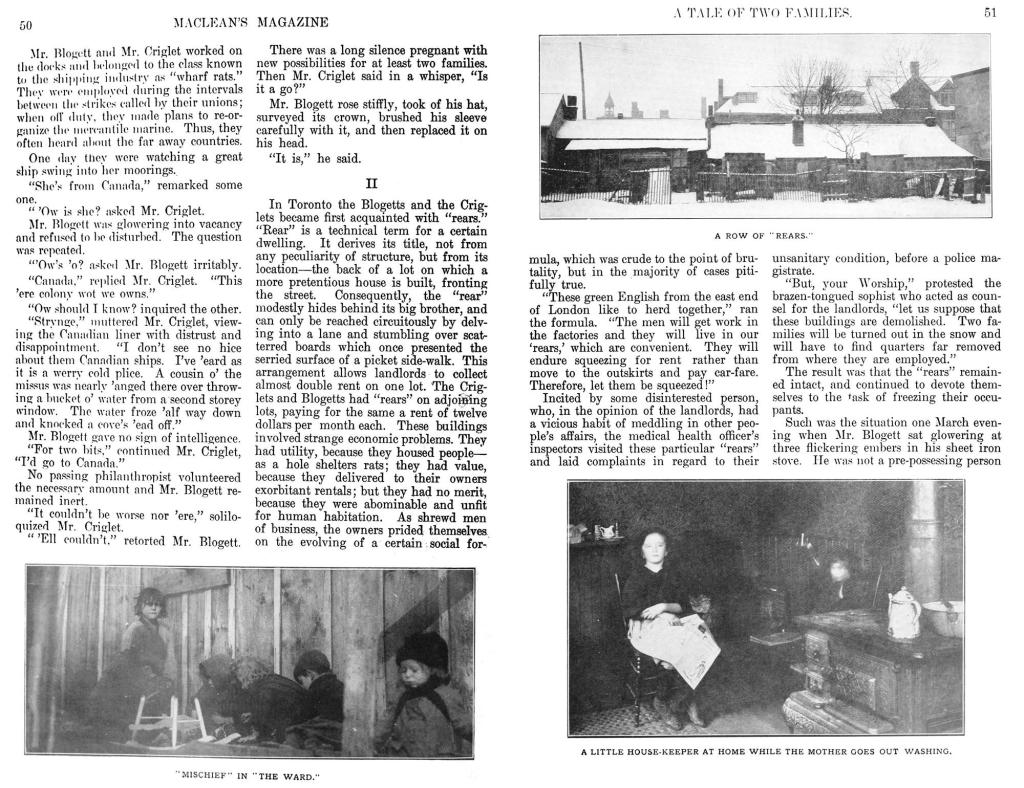

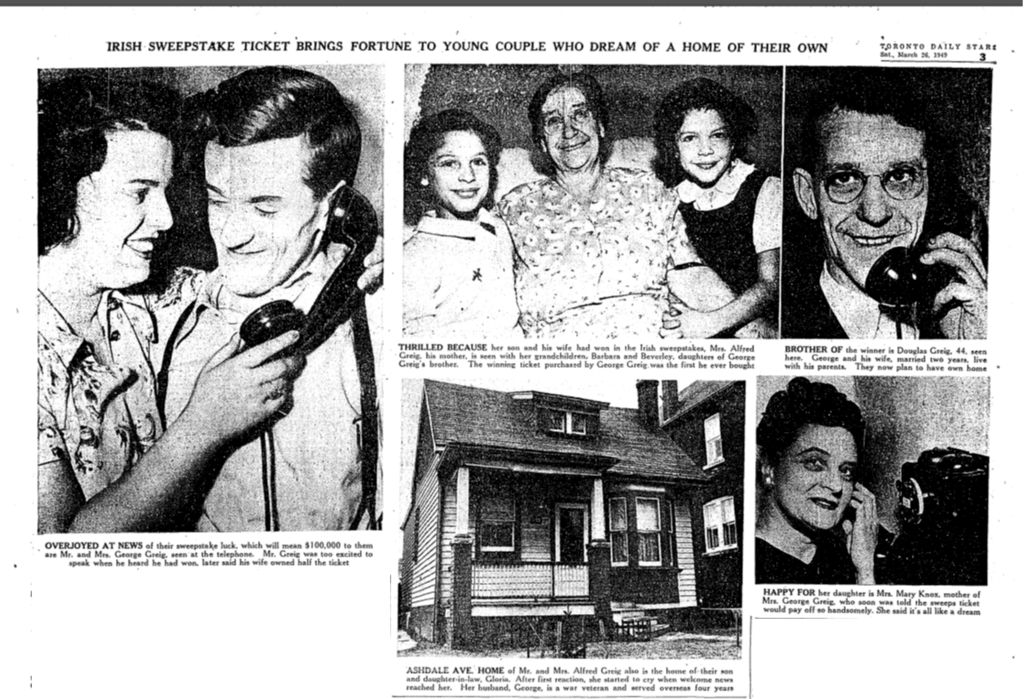

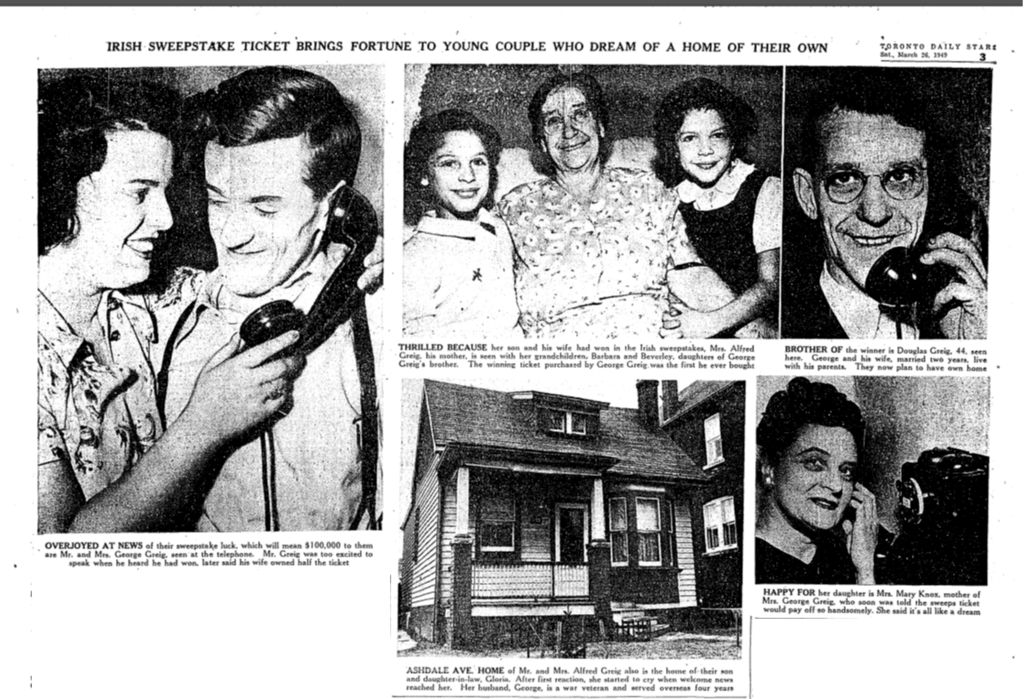

This story is about an immigrant family who went from living in a tarpaper shack in a Shacktown (like that of Gerrard-Coxwell’s neighbourhood). They worked hard and “made good” going from their humble home to a comfortable well-built house. When I was growing up outside of Toronto an immigrant family moved into a chicken coop next door to us. It was a tarpaper shack too, a smelly one at that. But the whole family worked hard and over time the tarpaper shack too became comfortable bungalow. Happy memories!

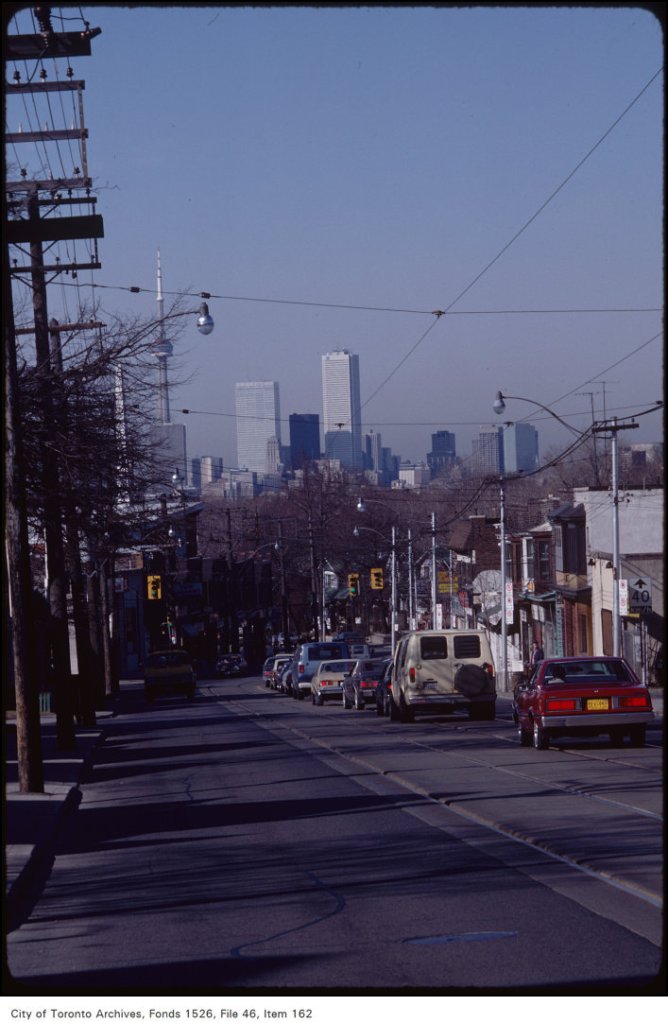

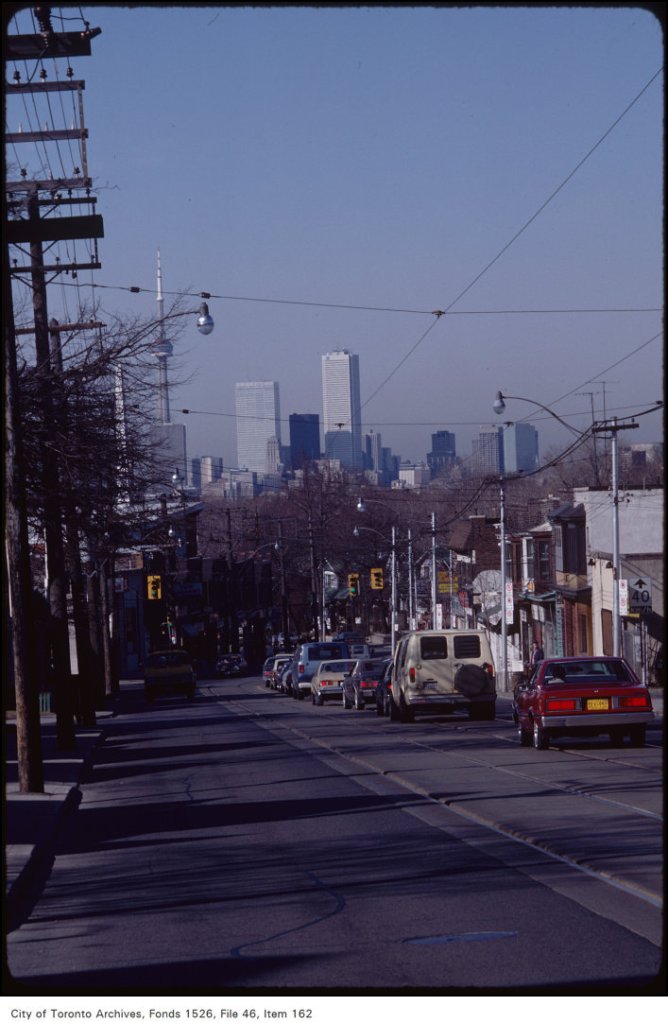

One of my happy spaces and a happy place for many of us.

And it makes me happier thinking of hard-working people who had a stroke of luck. A family in my village also won the Irish Sweepstakes. My mother always said, “Money can’t make you happy, but it sure can make being miserable a whole lot easier.”

Our local merchants have made my life happier over and over again.

And even on the darkest days, there are rainbows in the sky and on the sidewalk. I took this photo on Woodfield Road.

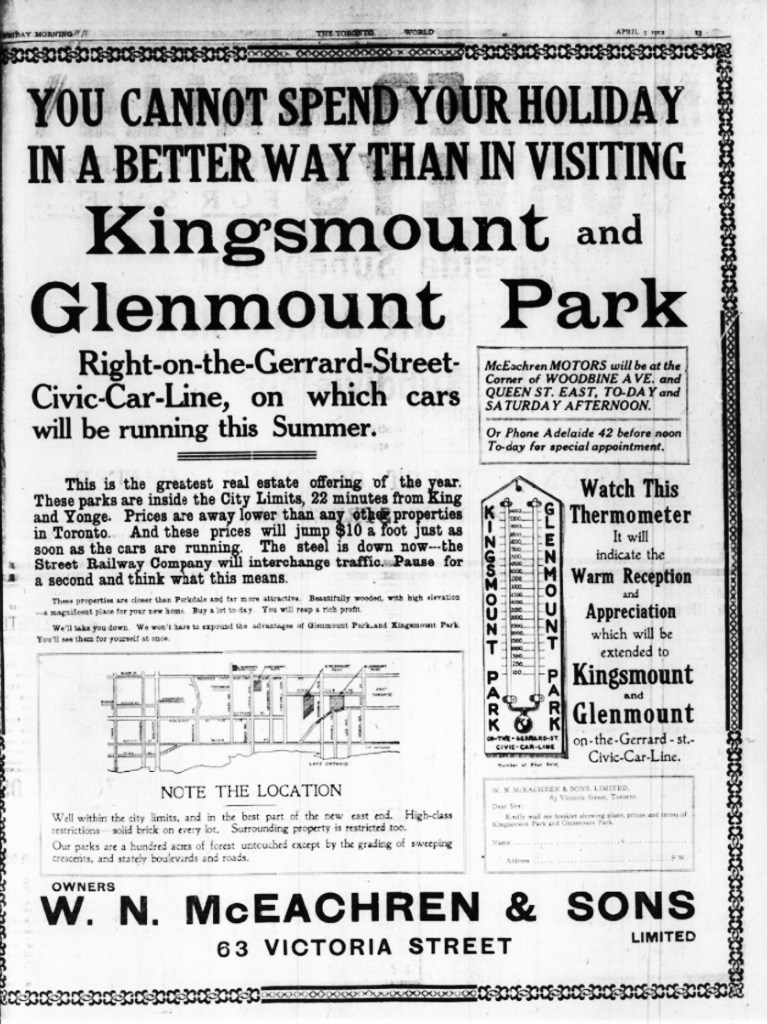

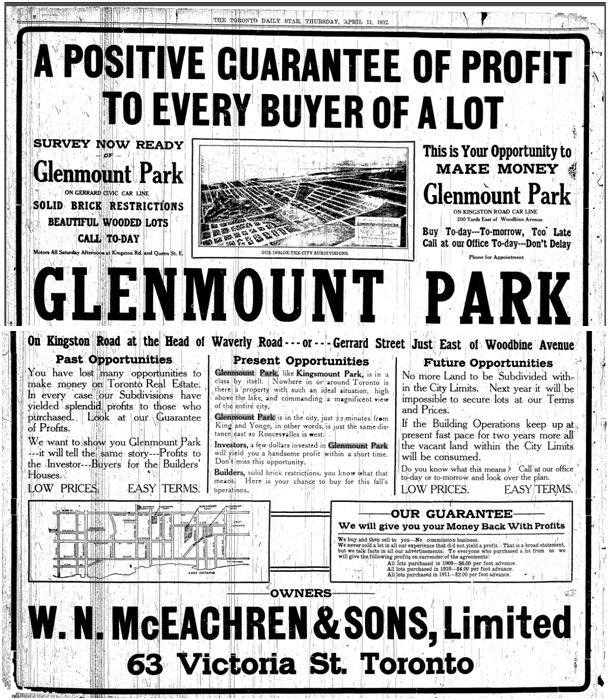

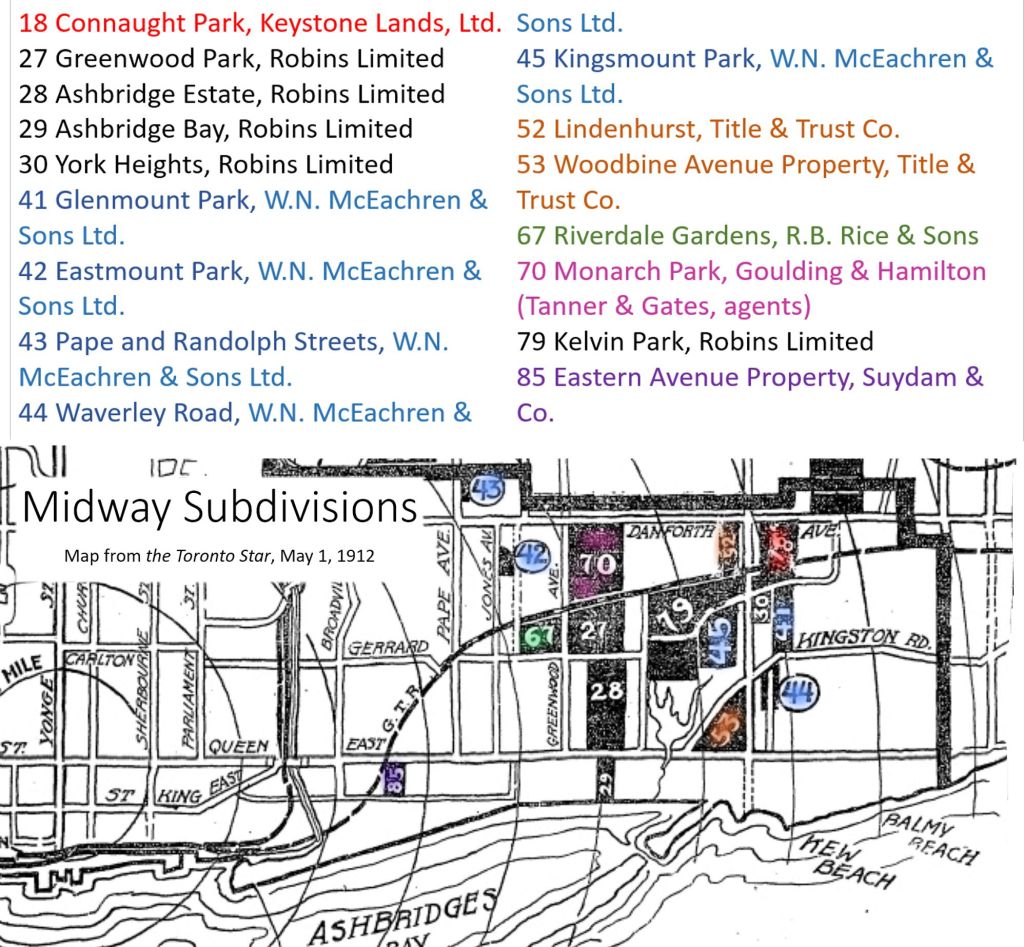

When the Ashbridges sold their farm west of the Toronto Golf Club grounds. F.B. Robins was their realtor. When Erie Realty Company sold lots on and just west of Coxwell Avenue, Frederick B. Robins was their realtor too. Henry Pellatt, F.B. Robins and their circle were known their free and easy approach to such things as insider trading, conflict of interest, and manipulating the markets.

While Robins and Pellat survived the Financial Panic of 1907, the crisis revealed the weaknesses of a largely unregulated financial sector.

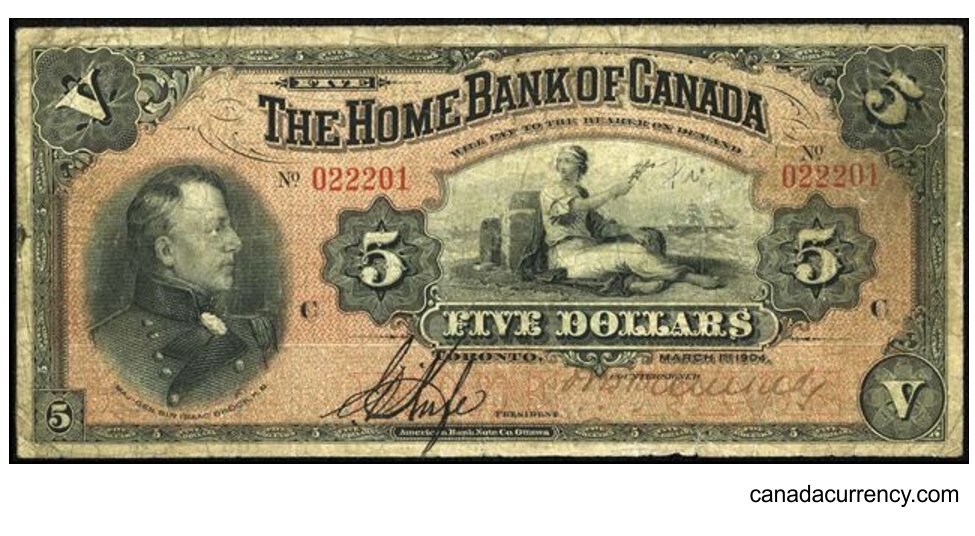

Five Canadian banks failed between 1905 and 1908. The failure, in January 1908, of the Sovereign Bank was the biggest, but not the last Canadian bank to fall. Bankers feared a domino effect. One of the banks Pellatt was involved with was the Home Bank of Canada, founded in 1903. It grew out of the Home Savings and Loan Company, created in 1854 to serve Toronto’s Catholics.

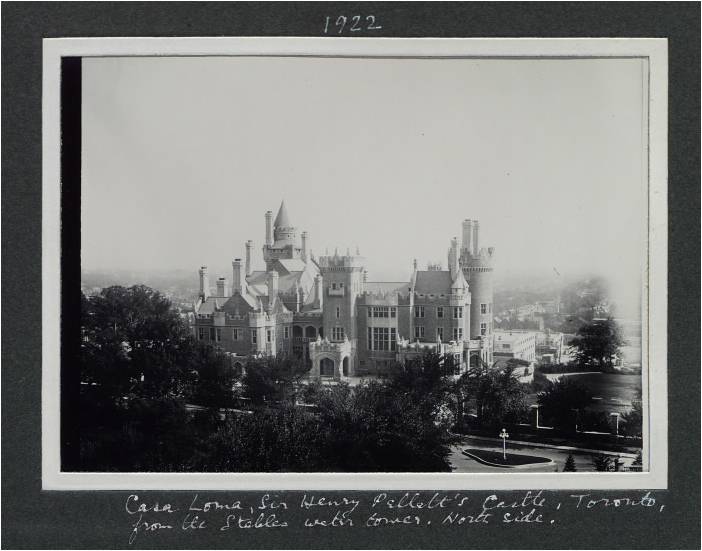

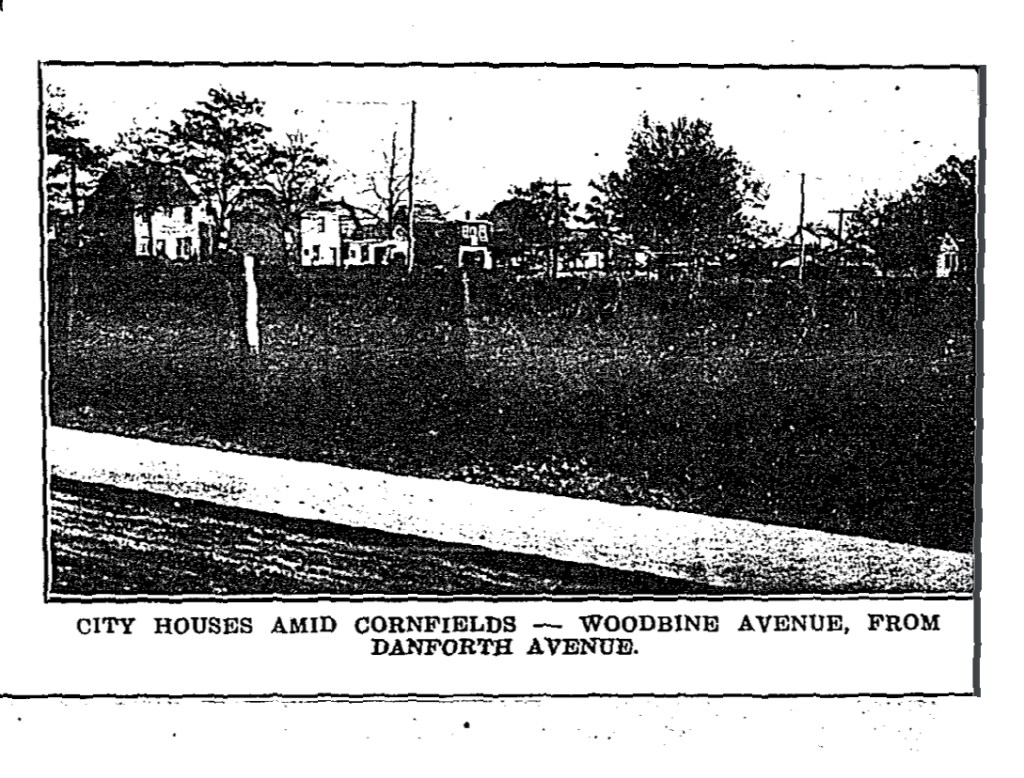

Pellatt with his castle, Casaloma, seemed to be Canadian royalty. But his wealth was built on offering risky investment opportunities to unsophisticated investors and using the savings of poor Irish Catholics through the Home Bank. Many investors in Pellatt’s enterprises were poorly equipped to evaluate risk and unable to afford losses. With this money, Henry Pellatt and Frederick B. Robins, both “land sharks”, bought up land on the fringes of Toronto and, in Pellatt’s own words, “nursed it along” until they could profit from the anticipated suburban growth.

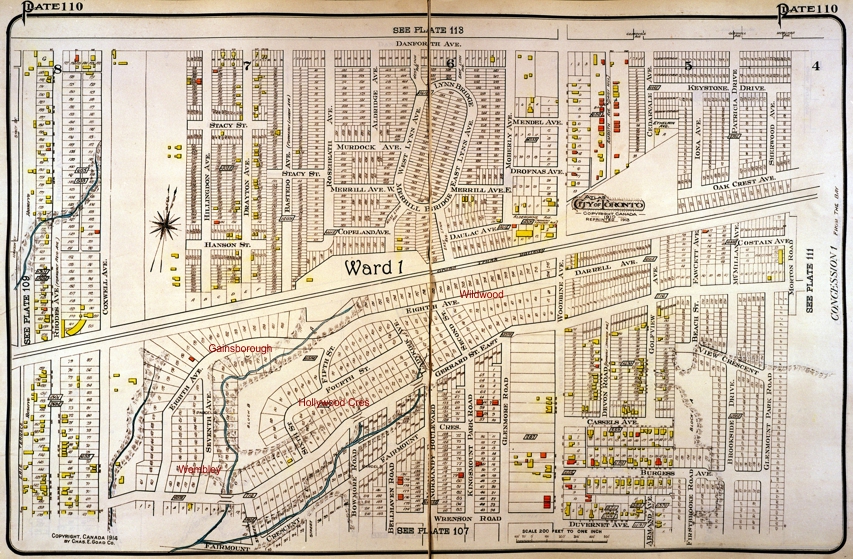

In 1909 the City of Toronto annexed the area south of the Danforth between Greenwood Avenue and the Town of East Toronto, allowing Toronto to expand eastward. Toronto City Estates incorporated in a partnership that would make Frederick Robins the real estate agent for almost all sales from Greenwood to Woodbine Avenues. Pellatt was a director of the Home Bank which lent millions to the Pellatt’s enterprises apparently without the knowledge of other directors.

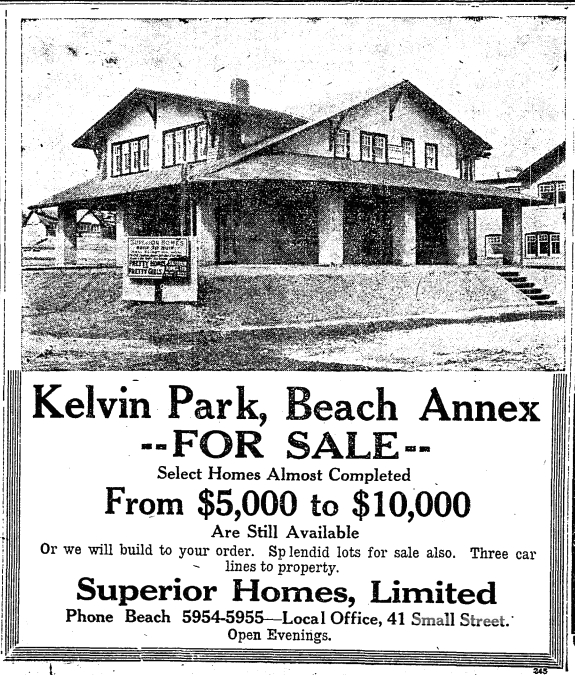

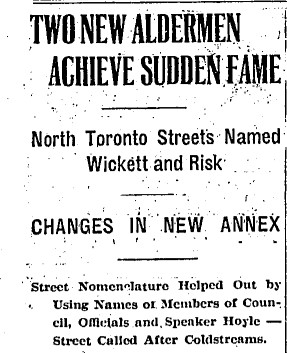

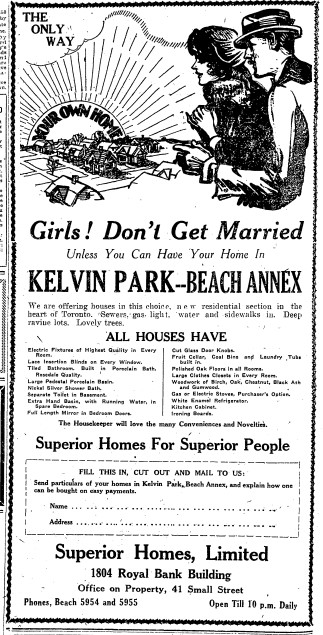

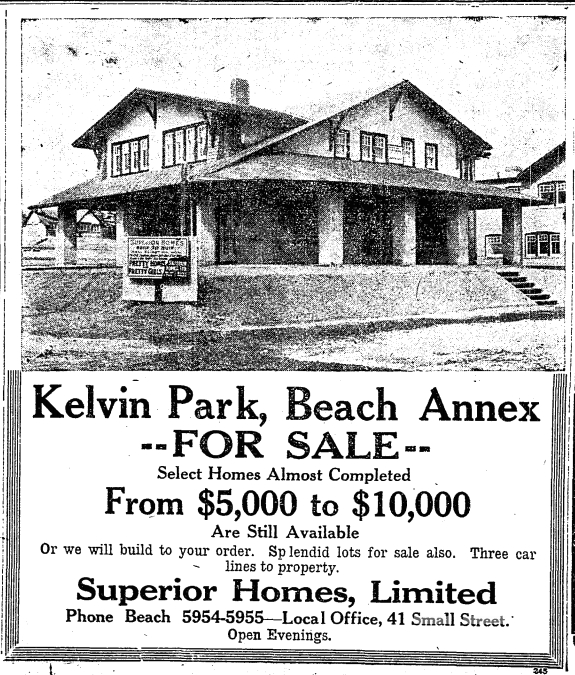

A genius in marketing, Pellatt renamed the Toronto City Estates subdivision on the Toronto Golf links. Its new name, Kelvin Park, suggested modernity and electricity. William Thomson, Lord Kelvin, died in 1907 the same year that Adam Beck brought Niagara’s electricity to Toronto. William Thomson was instrumental in the laying of the Atlantic Telegraph Company in 1856. This scientist, with his interest in the transmission of electricity. became a hero of the day and was knighted for his efforts, become Lord Kelvin. Kelvinator appliances (fridges, stoves, etc.) took their name from Lord Kelvin too.

Although favourable reports of Kelvin Park appeared in the British press, sales were slower than anticipated as another economic downturn preceded the First World War.

By 1914 the Home Bank was in deep trouble. Other bankers blamed Home Bank’s troubles on inefficient management and complained to the federal Minister of Finance. The Government of Canada refused to investigate the Home Bank, fearing this would cause the Bank to fail and destabilize credit vital to the war effort. The Bank promised to change and to reorganize its Board of Directors. However, the economy slumped after World War One. The Home Bank struggled on. Others went under went under.

In 1919 Standard Reliance Mortgage Corp., along with its subsidiaries was insolvent. F.B. Robins was the major stockholder in Dovercourt Land Company, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Standard Reliance. Yet Frederick B. Robins managed to survive and continue dealing in real estate.

In 1923 a housing boom started to fill the area with homes. But it was too late for Henry Pellatt. On August 17, 1923, the Home Bank suspended operations. The misstatements on the financial reports and other deceptive practices added up to a disaster for depositors. The Bank over-valued its collateral which was mostly real estate, and, on this shaky basis, loaned money. Home Bank’s liabilities far exceeded its assets. There was little actual cash in the Bank’s own account. Nearly $2 million dollars was loaned by the Home Bank to Toronto City Estates. Sir Henry Pellatt was both the President of Toronto City Estates, and a director of the Home Bank. Loans were secured by the Bank’s and its subsidiaries worthless stocks, as well as overvalued properties and mortgages.

Sir Henry Pellatt was a broken man. His wife died, he lost his castle, and he ended his days living with his former chauffeur in a small Etobicoke home. F.B. Robins emerged unscathed and went on to be appointed as a diplomat representing Canada abroad.

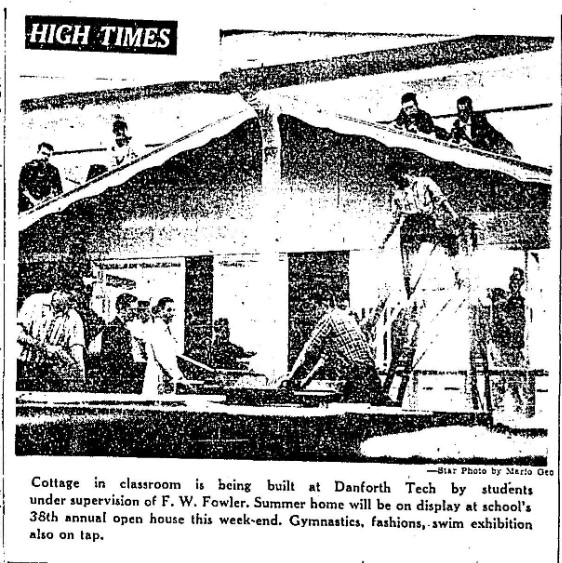

Providential Investment Company and Superior Homes took over the sale of Kelvin Park. Sales skyrocketed and houses went up to line the streets where they still stand today. Two show homes graced Kelvin Park: a classic Arts and Crafts bungalow and a hip-roofed home, known as “the Electric House”, used to showcase electric lighting, heating, and appliances. Sales of electric appliances and homes skyrocketed. Although the name Kelvin Park has been forgotten, the houses built from 1923 to 1929 still line the streets that lie where the greens and fairways of the old Toronto Golf Club were.

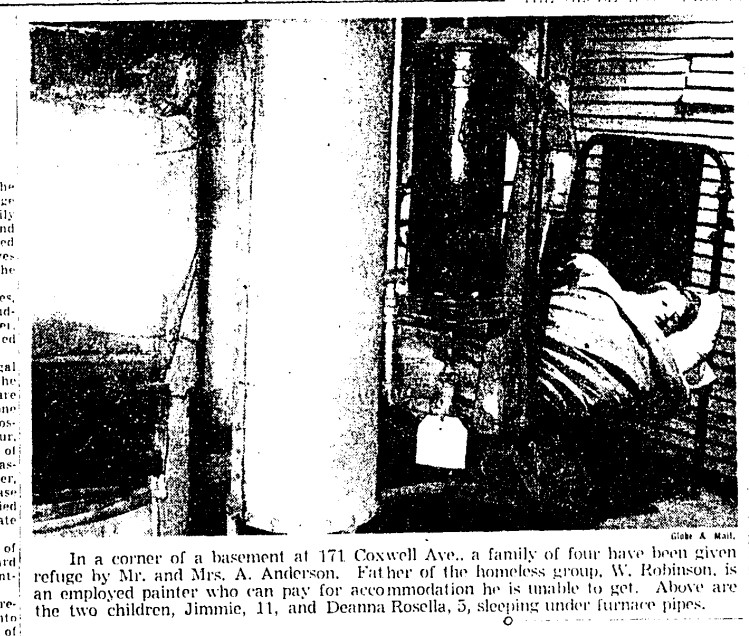

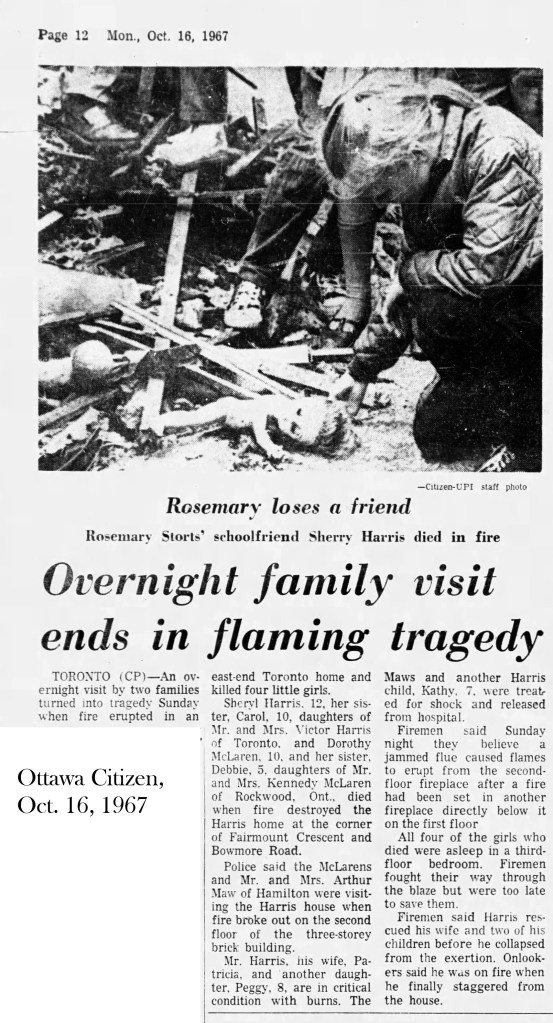

As I research the history of the neighbourhood from the beginning of the 20th century when the Ashbridge’s and Small estates were broken up for housing, I’m struck by just how many fires there were. This makes sense at a time when many houses were tarpaper shacks, built closely together in Shacktowns and even more substantial houses were had roofs of wooden shingles. Coal and wood fueled furnaces and chimney fires were common. So I’m posting some of those fires street by street. I start with Vernon Pankey on 2100 Gerrard Street East, injured in a fire on February 21, 1948, four years before I was born.

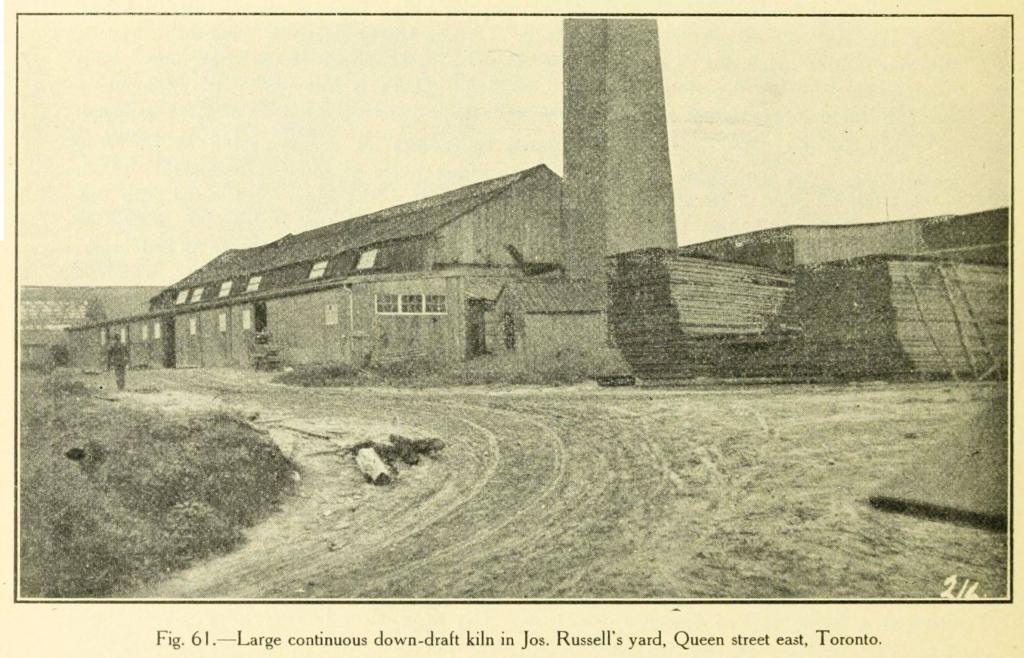

I am focusing on residential, business and some small factory fires. Brickyard fires were so common that they deserve a post of their own.

William “Stinky” Harris’s glue factory at Coxwell and Danforth was susceptible to fire as fats and oils rendered from animal carcasses are very inflammable. Sometimes our neighbourhood even appeared in the Big Apple news: Losses by Fire. Toronto, Ontario, Sept. 22—Harris’s glue factory, on Danforth Avenue, was completely destroyed by fire this morning. Loss,$25,000.00; partially insured. New York Times, September 23, 1900.

The glue factory on Danforth Road burned down on September 22, 1900, causing about $6,000 worth of damage, a considerable sum at the time. The factory was a three-story brick building, 125 feet long and 60 feet wide, just outside the city limits, on “glebe land”. About 40 men were thrown out of work by the fire. Toronto Star, Saturday, September 22, 1900

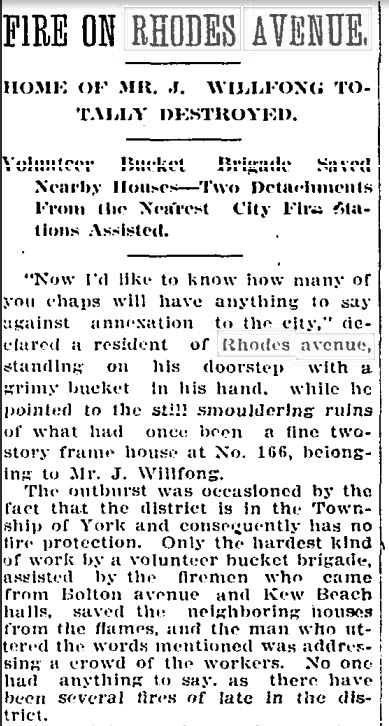

WIllfong fire, Globe, January 4, 1909

At the time Erie Terrace (later renamed Craven Road) was too narrow for the City’s fire trucks to drive on. So this narrow street, known as “Bootlegger’s Alley”, with shacks packed in side by side was particularly vulnerable to conflagrations that could quickly spread from house to house.

Brush and grass fires were common. Embers and coals flying off of the trains started many such blazes, but people also set fires to clear weeds and overgrowth as well as leaves in autumn. Sometimes they got out of hand. As well children playing with matches and the occasional arsonist played a role.

Belle Ewart was an ice company that used teams of horses to deliver ice across the city. Stables were and still are very vulnerable to fires with lots of hay and straw. Sometimes in hot weather fires even started by spontaneous combustion. And horses are notorious for panicking in a fire and need expert help to get out or they will run back into the flames. A barn or stable makes a death trap for livestock, horrifying to watch.

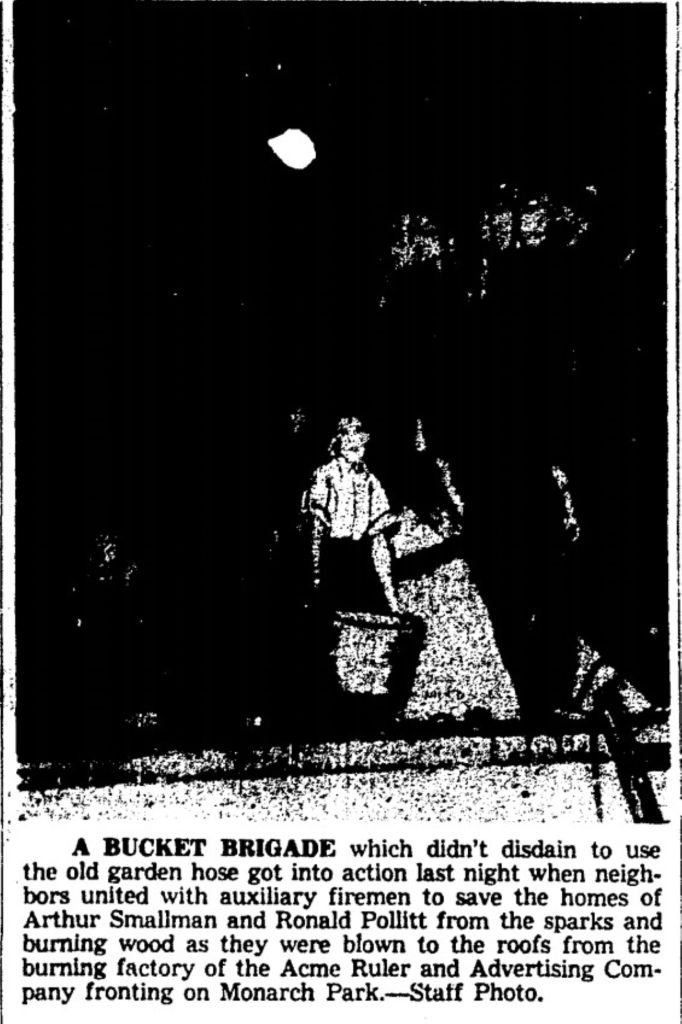

Below: Fire at the Acme Ruler Company, Globe and Mail, June 11, 1942

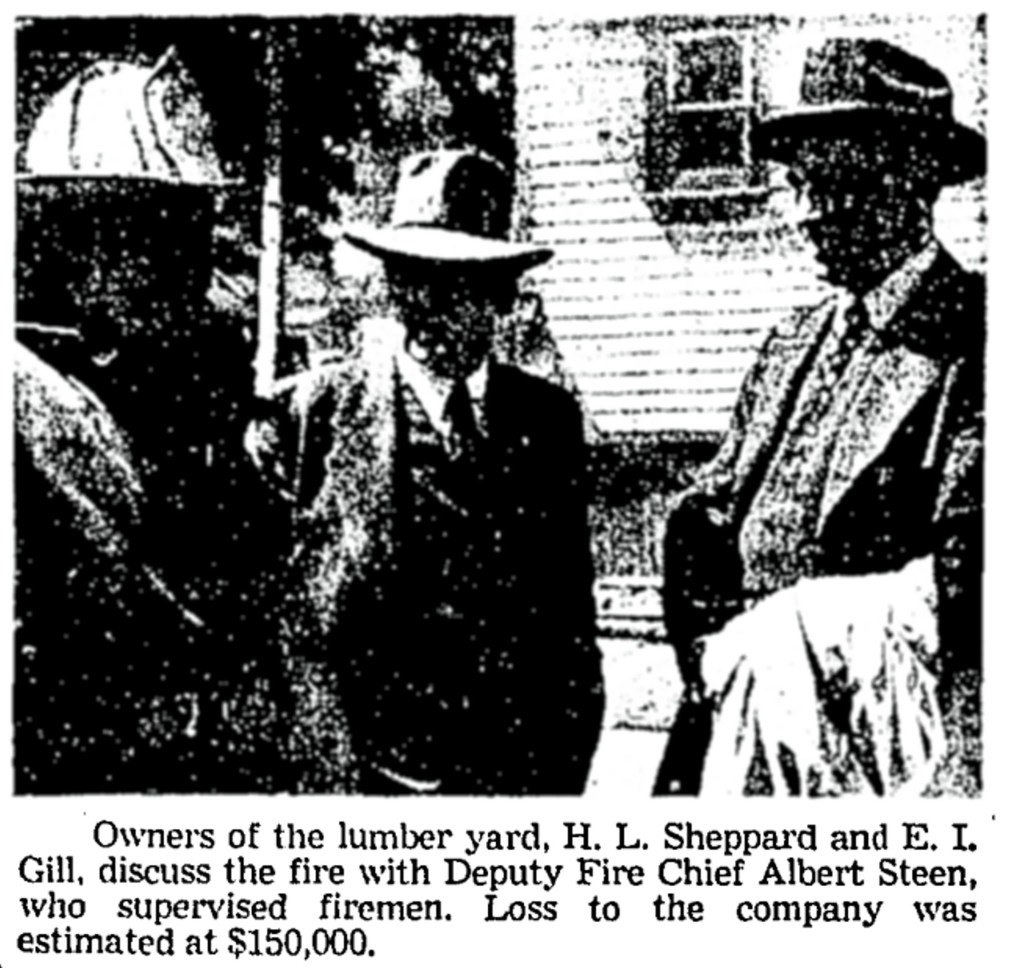

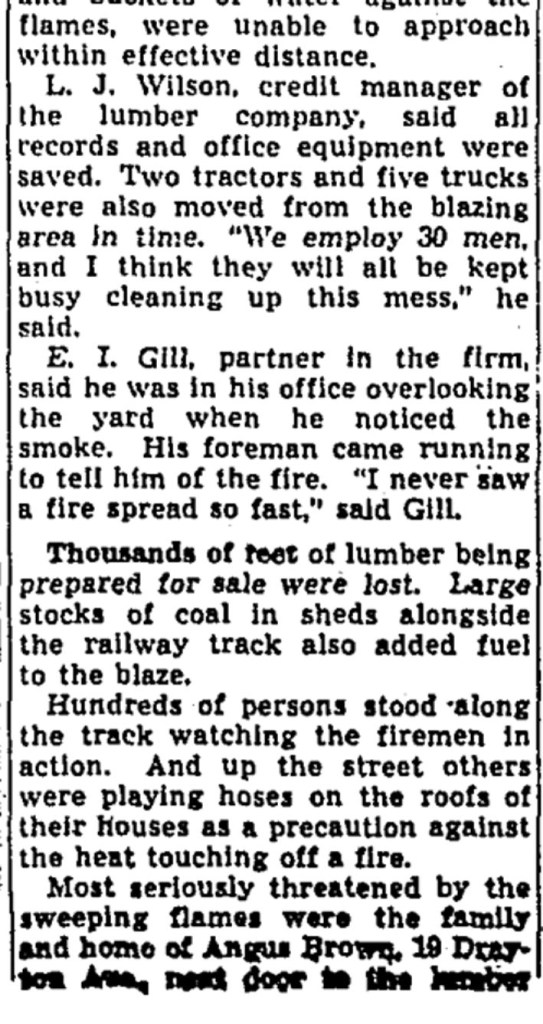

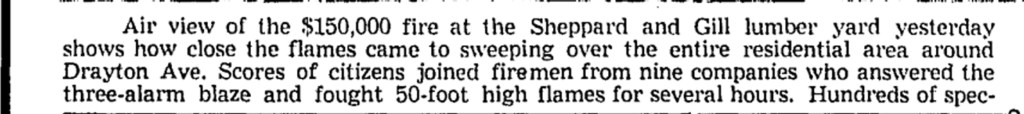

Some fires like the one at the lumberyard at Drayton and Hanson Street in May 1948 were spectacular. But in this case neighbours worked together to save each other’s property and lives too.

Fires at Christmas were common with highly combustible trees and decorations. Even if the only victim was a budgie, it would have traumatized the children. (I know. My home burned when I was in Grade Three.)

Generally my coverage of historical events ends in the early 1970s because of copyright restrictions. It’s not that fires stopped happening.

The brickmakers of the area were a tightly-knit group, intermarried and mostly Methodist by faith. Many, like the Prices, came from Bridgwater in Somerset, England. The Prices married into the Simpson family as well as the Kerrs and Billings.

When Lilia Lyla Billingsley Reed was born on December 21, 1890, in Todmorden, East York, Ontario, her father, Henry, was 30, and her mother, Mary, was 29. They were market gardeners. She married Frederick Simpson Price on July 7, 1910, in Toronto, Ontario. He was a brick manufacturer and built a sturdy Edwardian classic style home for his wife at 666 Greenwood Avenue, no longer standing.

Frederick Simpson Price passed away in 1949. Lyla became a nurse and lived near other Prices on Logan Avenue (the Logans were also brickmakers). She died on June 1, 1971, at the age of 80 and like so many from Midway, is buried in St. John Norway Cemetery.

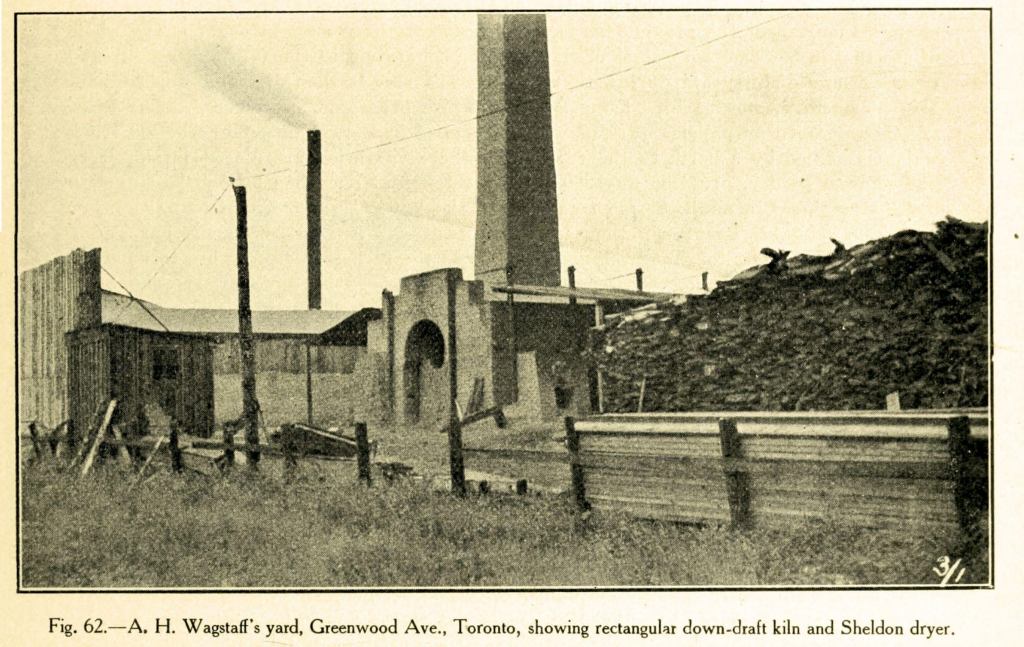

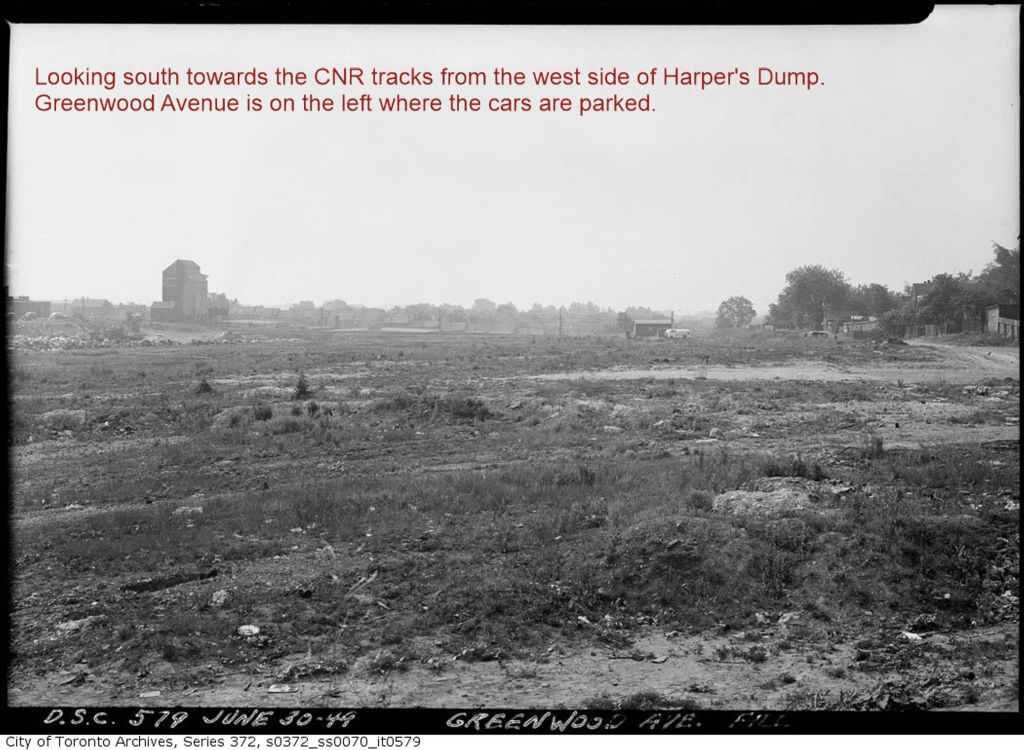

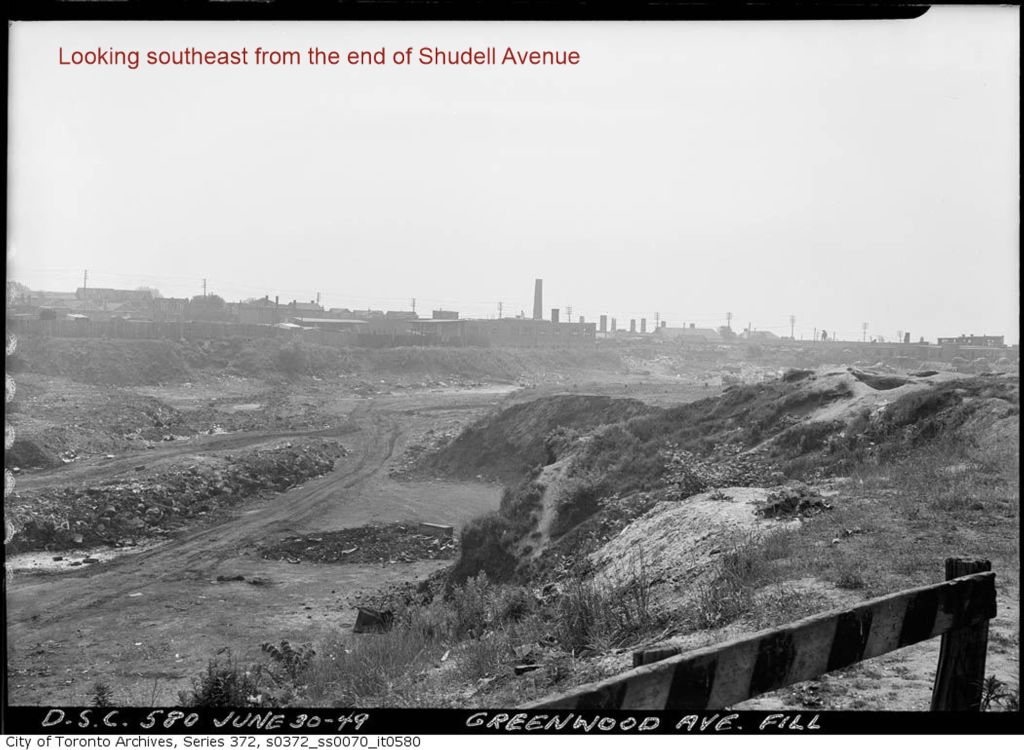

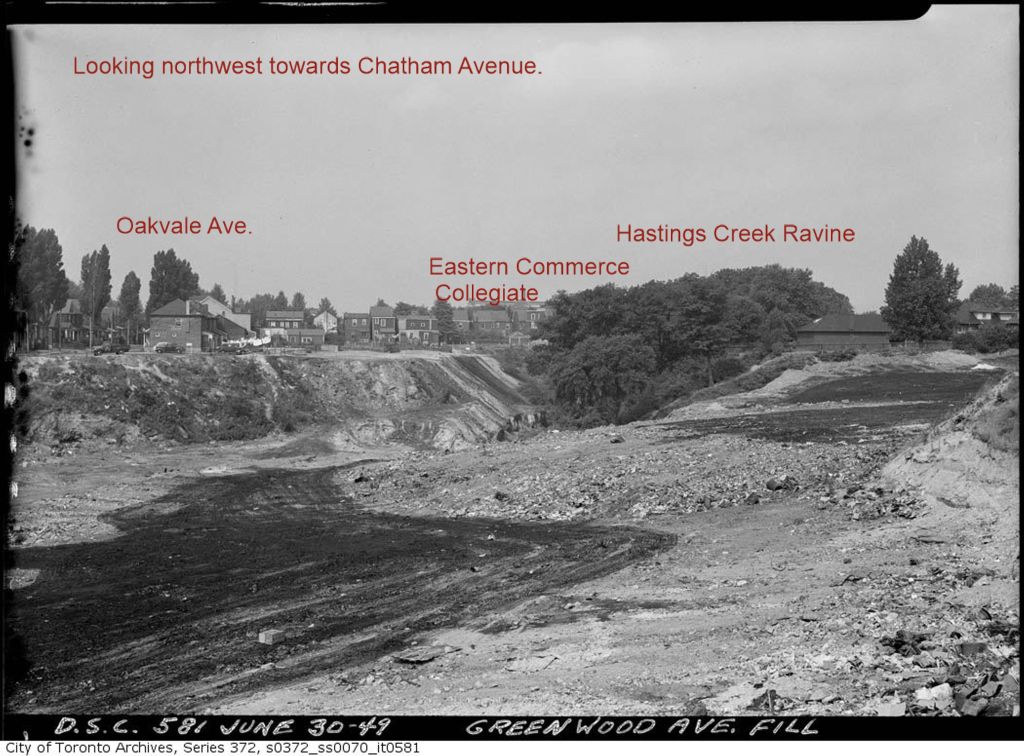

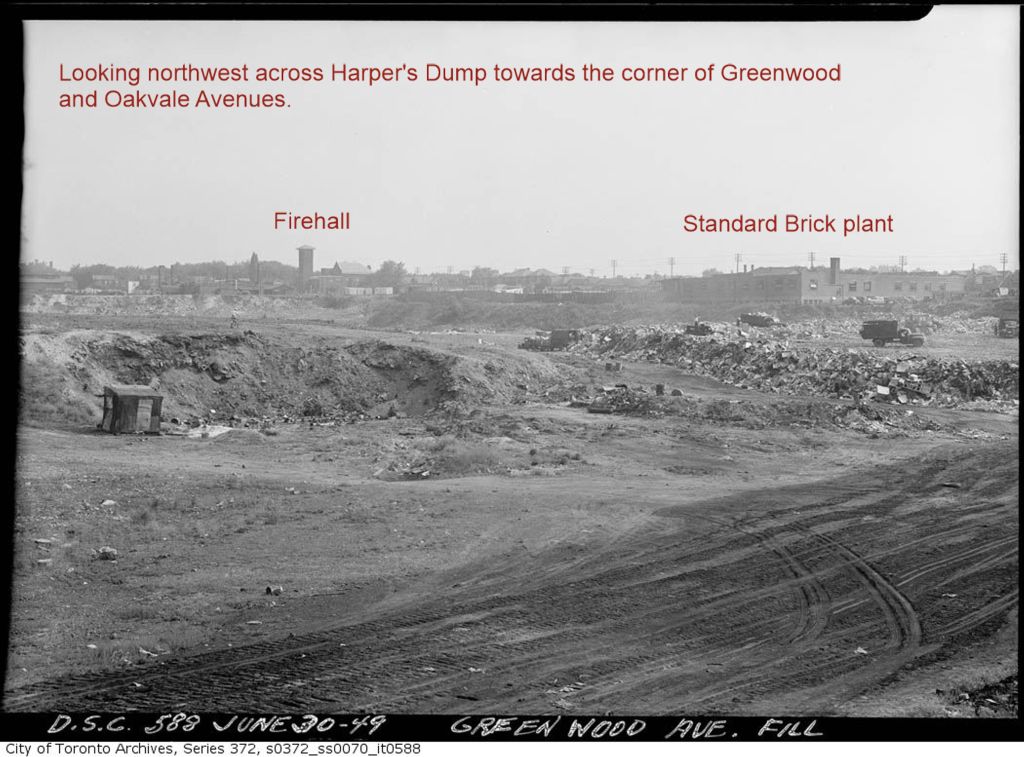

1930 By the 1930s, a combination of increased demand for bricks and mechanization of the brickmaking process depleted the brickfields. The only brickyard left operating was Price’s yard at 395 Greenwood Avenue. It became the Toronto Brick Company and closed in the 1950s. Torbrick Road, though a housing project, sits on the site of the yard.[1] The derelict brickyards became subdivisions, schools and parks. Morley’s brickyard became Greenwood Park. The Wagstaff brickyard on Ashbridges’ Creek south of Felstead later was filled in and became Monarch Park. Felstead Park was also a brickyard. The playing field of St. Patrick Catholic Secondary School is also a rehabilitated quarry. Another Brickyard became first Harper’s Dump and then the Greenwood Subway Yards. Manufacturers used other brickyards for factories.[2]

[1] Myrvold, Barbara. The Danforth in Pictures: A Brief History of the Danforth. Toronto: Toronto Public Library, 1979, 17.

[2] Myrvold, Barbara. The Danforth in Pictures: Avenue Brief History of the Danforth. Toronto: Toronto Public Library, 1979, 17.

Professor Coleman on the clay deposits:

The extent of these deposits has not yet been worked out in detail, though the lower stratified clay was apparently widespread. Twenty feet of clay very like it, containing thin layers of peaty matter, may be seen on the shore of Lake Ontario four miles to the east of Highland Creek, here also covered by a bed of till. Exactly similar clay occurs about four miles to the northwest of Victoria Park in the brickyards of Messrs. Price and Logan. The exposures are excellent, one presenting a face of sixty feet; and the top of the clay, which rises about one hundred feet above Lake Ontario, is covered with a few feet of stratified sand. One finds the greenish plate-like concretions, and peaty matter containing mosses, pieces of bark and wood, elytra of beetles, flakes of mica, etc., just as at Scarboro’. The layer of till is wanting at these brickyards, but is found a few hundred yards farther north near the corner of Danforth avenue and Greenwood lane.

Coleman, A.P. Glacial and Inter-Glacial Deposits Near Toronto,Photograph. A.P. Coleman. Price’s Brickyard (Toronto). 1924 ROM Archives. A.P. Coleman Collection Reprinted from The Journal of Geology, Volume III

, Number 6 September-October, 1895. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, p. 631.

1965 The Toronto Planning Board approved a 1,404-suite apartment and town house complex on the site of an old brickyard on Greenwood avenue. Nine apartment buildings from 9 to 22 storeys and five clusters of townhouses were approved along with a small shopping mall. Torbrick Investments Ltd. were asked to buy up the remaining Greenwood Avenue properties adjoining the site. The Board also wanted some kind of central heating plant to supply heat for all the buildings and thereby reduce pollution. The CN tracks bordered the south end of the site. Therefore, the planners also wanted an earth berm between the tracks and the buildings to reduce noise. The site was a 16-acre brickyard, on the east side of Greenwood Avenue, south of Felstead Avenue.[1] Local residents protested against the proposed apartment and townhouse complex in the old Torbrick yard on the east side of Greenwood Avenue, fearing that the increased demand on local schools and recreational facilities, and the growth in traffic would cause problems. Residents of Felstead and Greenwood Avenues went to the City Building and Development Committee to air their concern. They wanted the developer to provide a pool and rink because local playgrounds were already too crowded. They were also concerned about possible damage to their properties from pile driving, as had happened when the Greenwood subway yards were built.[2] The City of Toronto Board of Control approved zoning changes to allow a high-rise and town house complex in the old Price brickyard at Greenwood and Felstead. The developer had to consider heating all the buildings from one plant; acquire houses on Greenwood Avenue to increase park, and built a pedestrian path to provide access to Monarch Park. 5 per cent of the 18 acre development had to be a park.[3]

[1] Toronto Star August 27, 1965 Friday

[2] Toronto Star Thursday October 14, 1965

[3] Globe Friday August 27, 1965

1845 John Price was born in Somersetshire, England, son of William and Jane (Manchip) Price. His family, like the Morleys, were brickmakers for generations. He learned the business from childhood.[1]

1869 James Price, brick manufacturer, Leslie Street, was English and trained to be a brickmaker there. He came to Canada in 1869.[2]

1869 John Price came to Canada and become a farmer, but it wasn’t long before he became a brickmaker again. His first work as a brickmaker here was for William Plant, whose brickyard was at the foot of Niagara Street near the city’s abattoir. Plant and Price then made sewer pipe for a year, under the name of Plant and Price.

1870 John Price became manager for Lucas Bros., brickmakers, for two years.

1872 John Price went into partnership with John Lucas. The firm of Price and Lucas went on for six years until 1878.

1874 John Price went to visit England and returned with a wife — Jane Powell. They had the following children: George Powell (who married Emma Kerr), Isabella, Albert and Harold; Charles; Harry; Louisa (Lucy); and Susie Jane. The family was Methodist.[3]

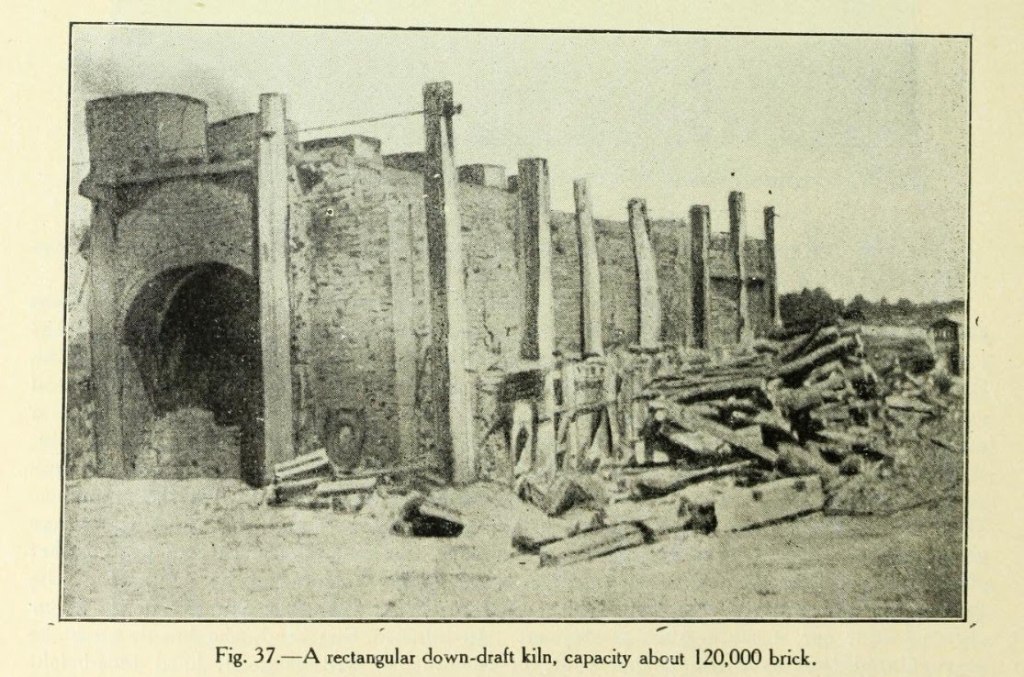

1878 The firm of Price and Lucas dissolved. John Price joined with others to found the Price & Co. brick manufacturers on Greenwood Avenue. It grew into one of the biggest in Canada with a reputation for an excellent facing brick: “the John Price”, still in demand today though hard to obtain. Soft-mud “John Price reds” were made by tempering a clay-sand mixture with up to 30 per cent water. John Price used the Martin brick machine which had 20 steel knives on a vertical shaft that pushed the clay down. Wipers mounted on this vertical shaft pressed the clay into a “press box”. A plunger forced the clay into a five-brick mould, filling it completely. Then it was ejected and an empty mould put in the machine. A Martin machine could make up to 3,000 bricks an hour. A filled mold was ejected as an empty freshly sanded mold was inserted. Small amounts of borax, ferro-red or manganese dioxide were added to the sand, as required, to produce the desired colour. The machine could produce up to 3m000 brick per hour, but usually production was in the vicinity of 2400 bricks per hour. John Price bricks, like the other Bricktowne bricks, were made in Ontario Size (2-3/8″h x 4″d x 8-3/8″l), different from brick sizes anywhere else in the world.

The 1878 brickyard employed about eight to ten men and had an output of 10,000 bricks a day. Horses were used to power the equipment. Price enlarged the yard until he turned out 43,000 bricks per day and employed over 40 men.

1884 John Price bought out the other investors and took control of the business.

1885 he employed eight to 10 men and made 800,000 to 900,000 bricks annually.

1916 John Price died May 27, 1916 and is buried in St. James Cemetery.

1928 The Brandon Brick Company of Milton, Ontario, and the John Price Brickyard on Greenwood Avenue amalgamated to form the “Toronto Brick Company”.

1956 United Ceramics Limited of Germany acquired the Toronto Brick Company, closing the Greenwood Avenue brickyard, the Leslieville area’s last brickyard.

1962 The Toronto Brick Company relocated the Parkhill Martin Brick Machine from the former John Price Brickyard to the Don Valley Brickworks to make soft-mud bricks for the “antique” brick market.[4]

[1] Commemorative Biographical Record Of The County Of York Ontario Containing Biographical Sketches Of Prominent And Representative Citizens And Many Of The Early Settled Families Illustrated Toronto :J H. Beers and Co. 1907

[2] History of Toronto and County of York Ontario. Vol. I. Toronto: C. Blackett Robinson, Publisher, 1885, 382.

[3] Commemorative Biographical Record Of The County Of York Ontario Containing Biographical Sketches Of Prominent And Representative Citizens And Many Of The Early Settled Families Illustrated Toronto :J H. Beers and Co. 1907

[4] Baker, M. B. “Clay and the Clay Industry of Ontario”. Report of the Bureau of Mines (Vol. XV, Part II). Toronto: 1906.

Catalogue of Don Valley Products. Toronto: The Don Valley Brick Works Limited, n.d.

Darke, Eleanor. A Mill Shall Be Built Thereon. An Early History of Todmorden Mills. Toronto: Natural History/Natural Heritage, 1995.

Goad’s Fire Insurance Atlas, 1910 and 1910 revised to 1923.

Montgomery, Robert J. “The Ceramic Industry of Ontario”. 39th Report of the Ontario Department of Mines (Vol. 39, Part 4). Toronto: 1930.

“Plant of the Don Valley Brick Works, Toronto”. Canadian Architect and Builder (April 1907).

Sauriol, Charles. Remembering the Don. Scarborough, Ont.: Consolidated Amethyst

Communications, 1981.

Simonton, Jean. “Former Toronto Brick Company, East York.” Typescript. January 28, 1986.

Unterman McPhail Cuming. Don Valley Brick Works: Heritage Documentation and Analysis. Prepared for Metropolitan Toronto and Region Conservation Authority. December 1994.