In these rather unhappy days I chose pictures from the last week of March that made me feel happier. I hope you enjoy them! Joanne Doucette

This picture is of Charles Coxwell Small, the Family Compact member who owned all the land from Coxwell Avenue to Woodbine Avenue and from Ashbridge’s Bay to Danforth Avenue. He used a wheelchair because he was partially paralyzed as the result of a stroke. His workplace, the old courthouse on Adelaide Street east of Victoria Street, made itself accessible with ramps so that he could continue in his job. We’ve changed a lot as a society since the mid-nineteenth century and I’m glad of that too. As a person with a disability I need ramps and elevators and, basically, any place with stairs is off limits to me. The world is a happier place for inclusion, equality and diversity.

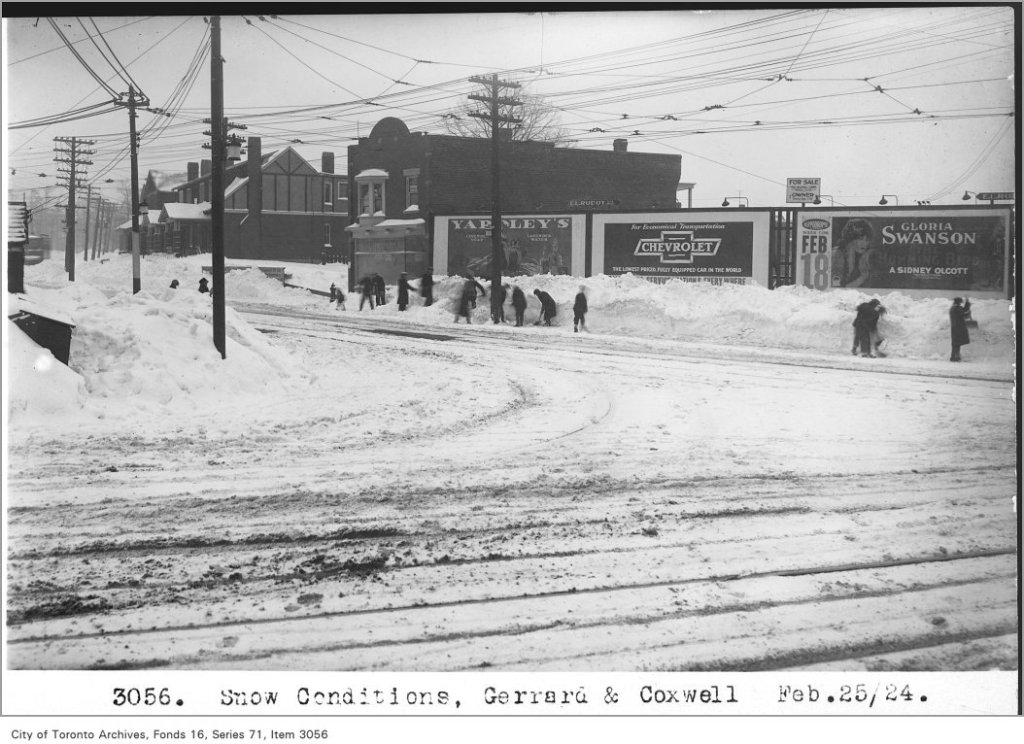

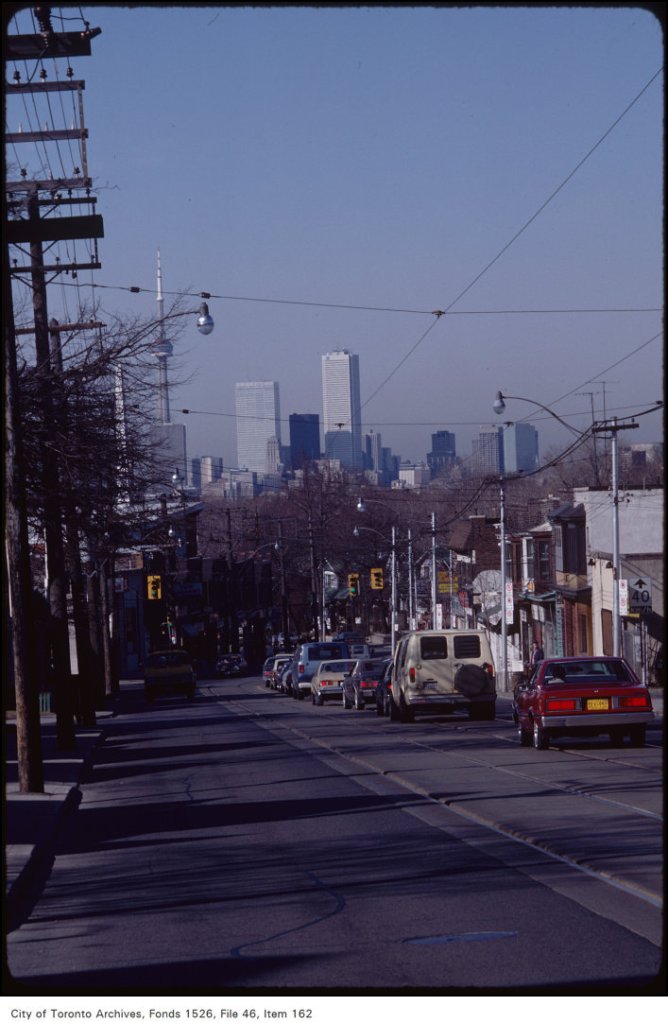

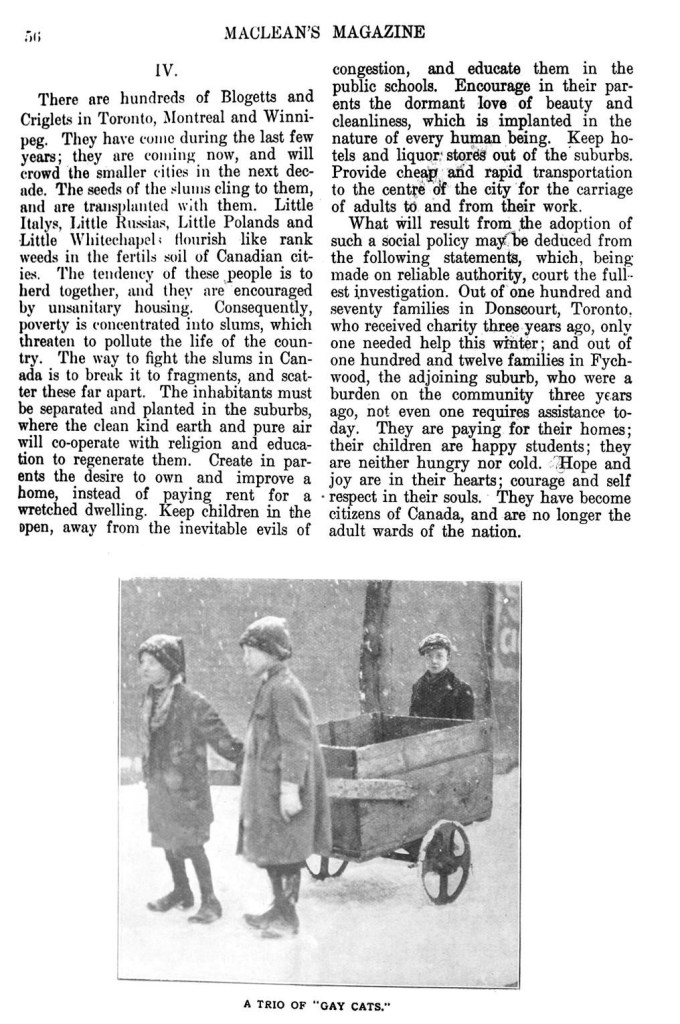

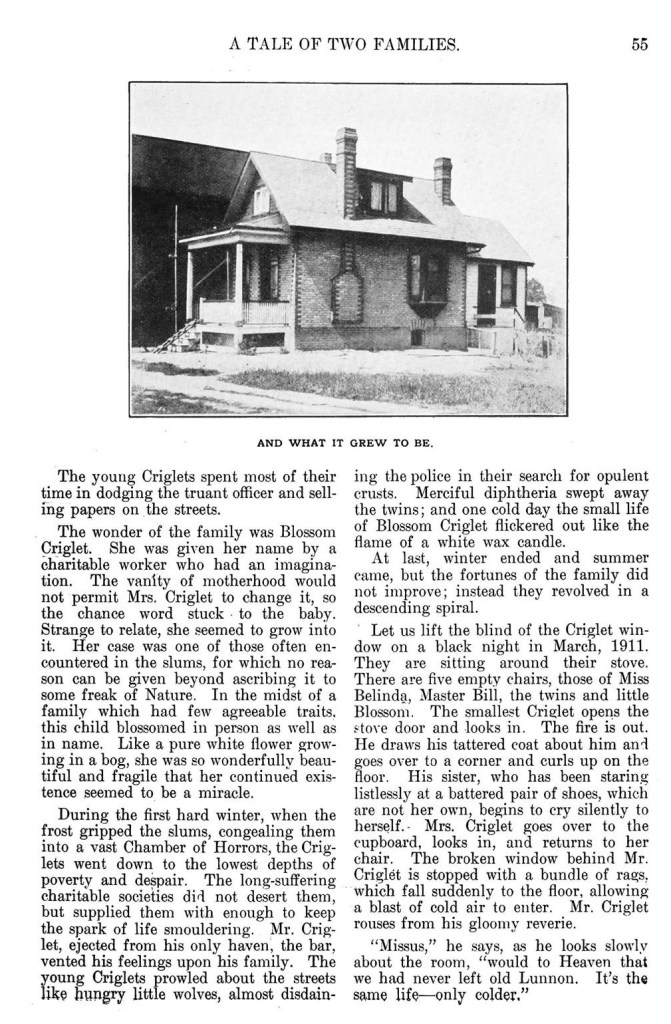

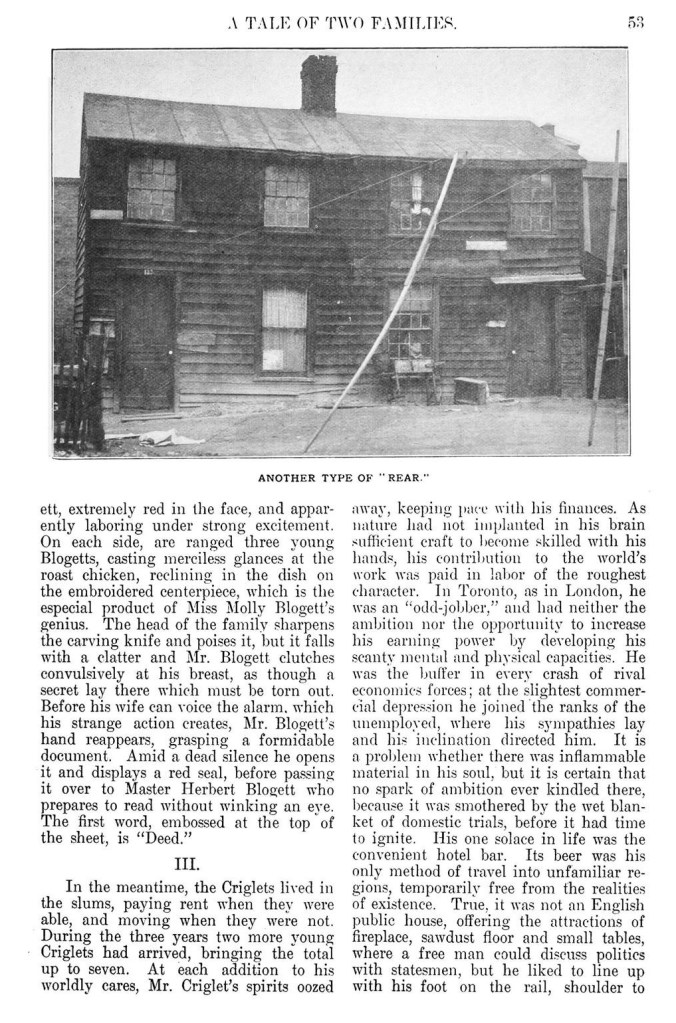

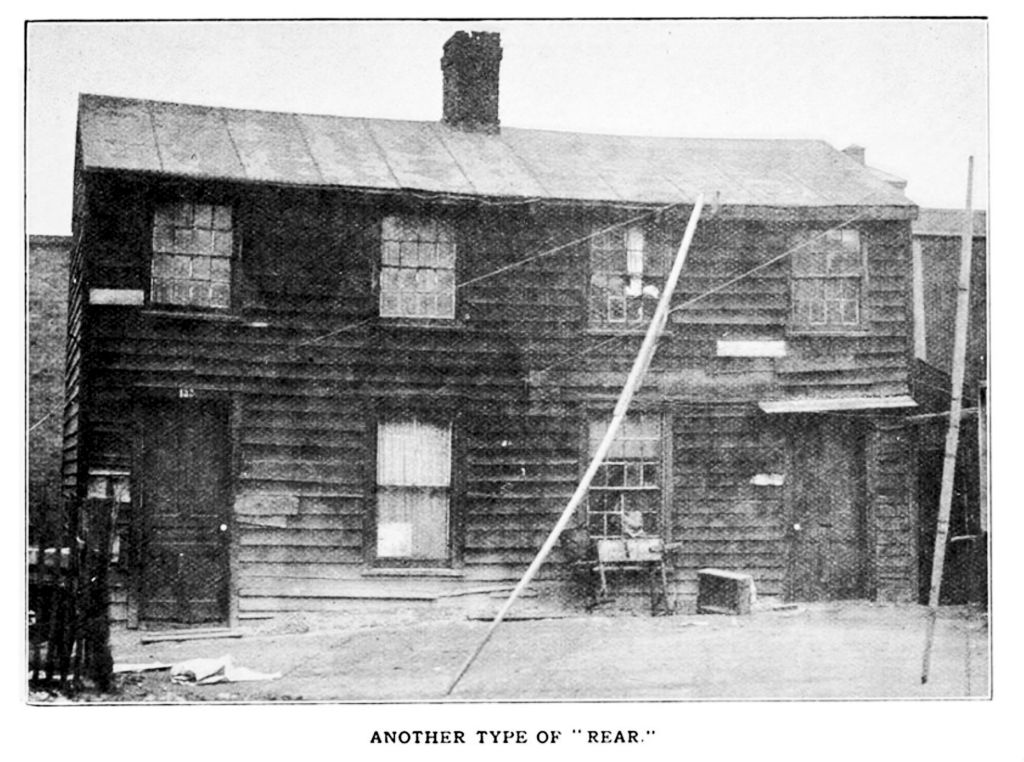

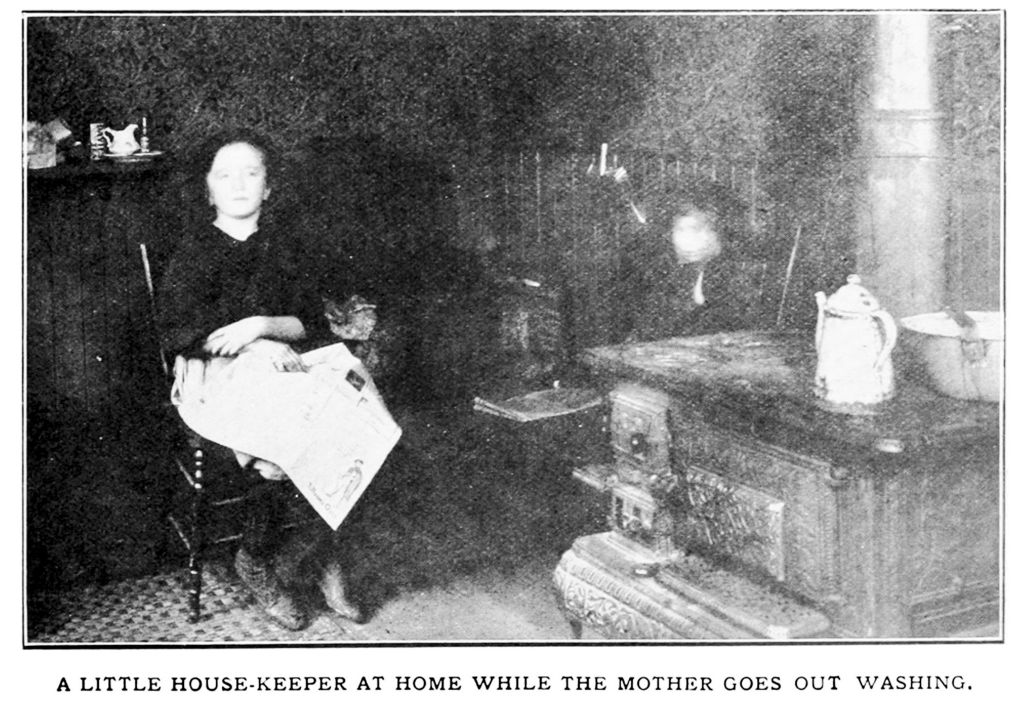

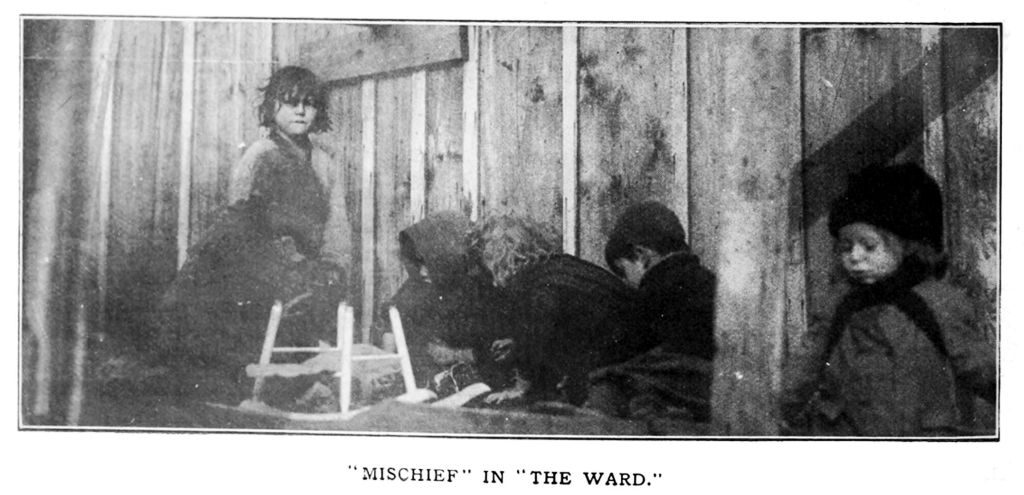

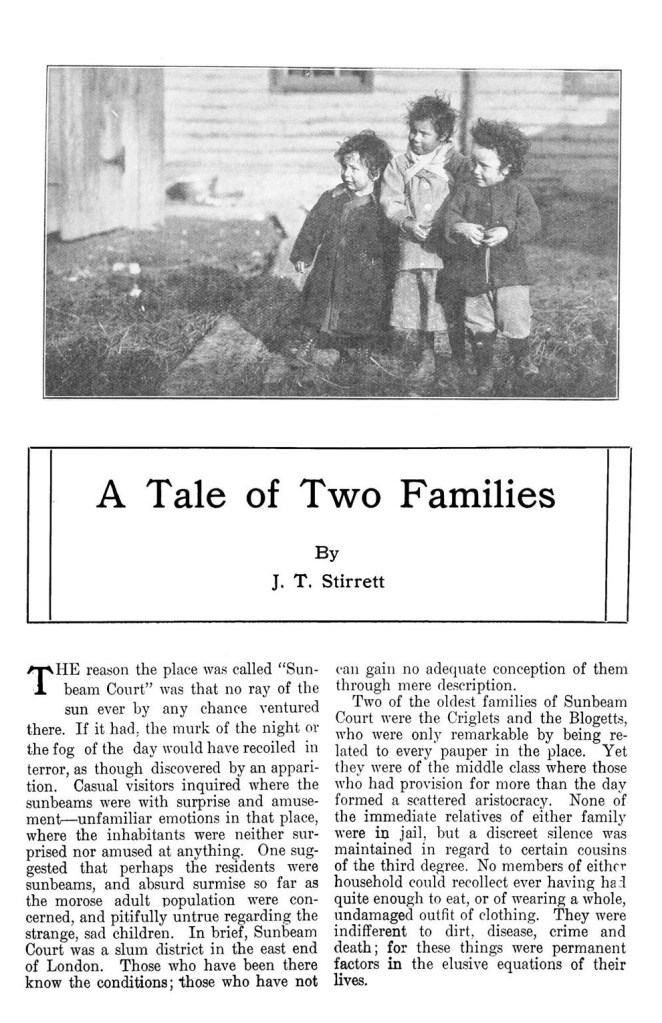

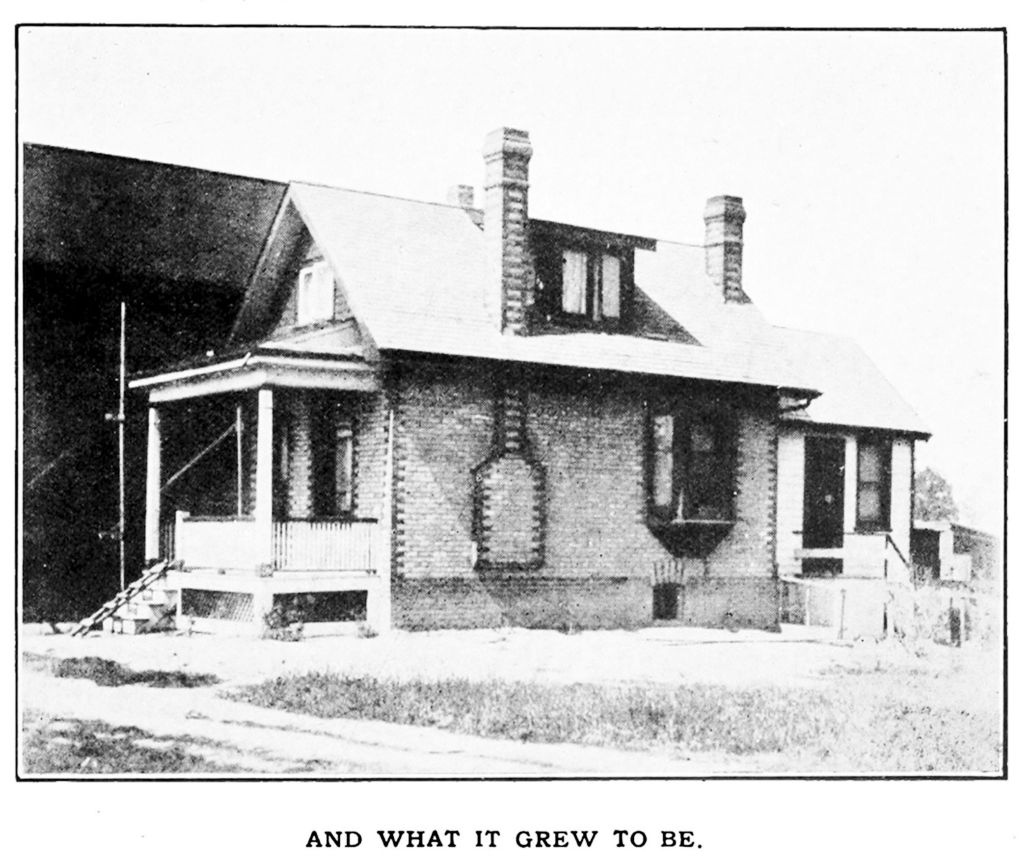

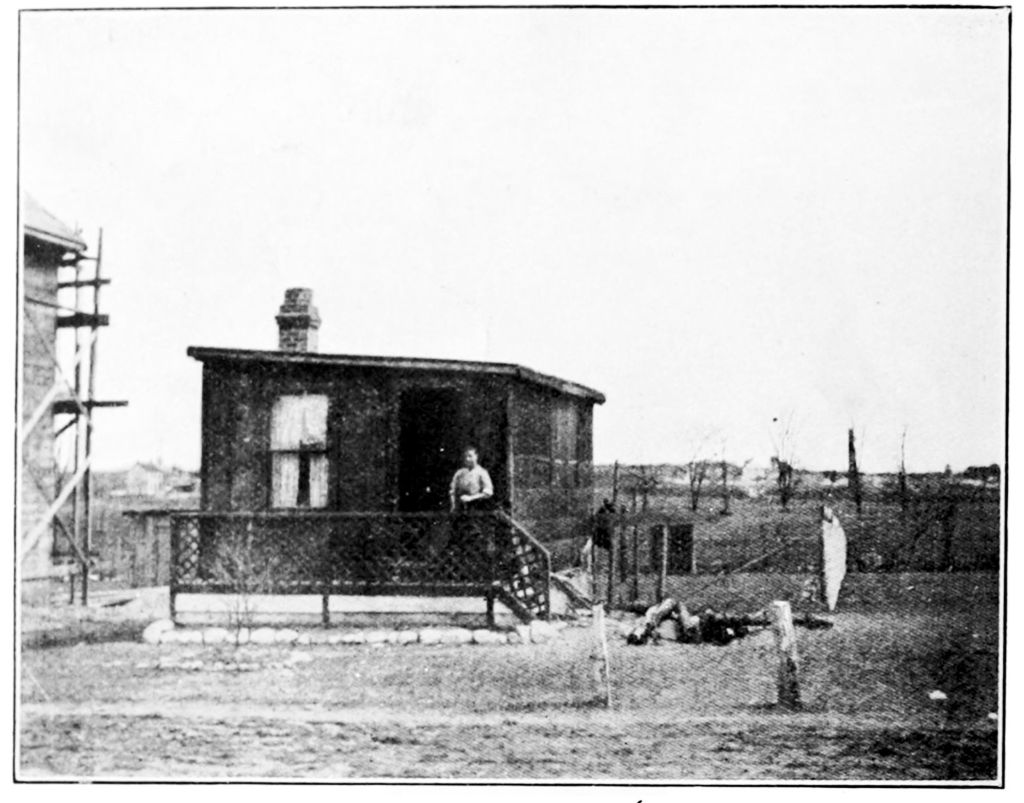

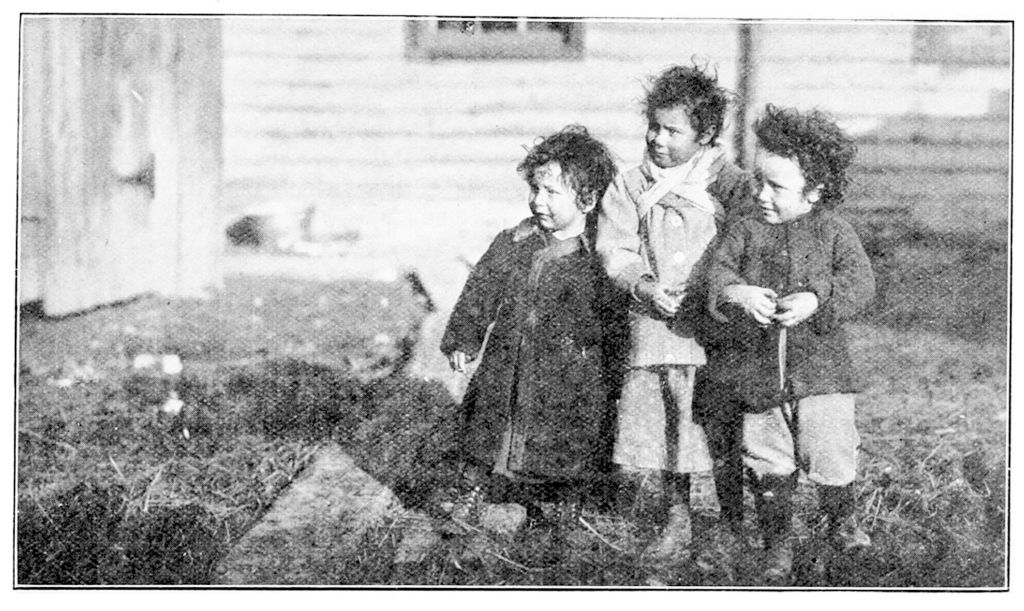

This story is about an immigrant family who went from living in a tarpaper shack in a Shacktown (like that of Gerrard-Coxwell’s neighbourhood). They worked hard and “made good” going from their humble home to a comfortable well-built house. When I was growing up outside of Toronto an immigrant family moved into a chicken coop next door to us. It was a tarpaper shack too, a smelly one at that. But the whole family worked hard and over time the tarpaper shack too became comfortable bungalow. Happy memories!

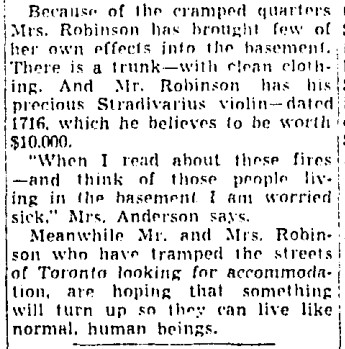

One of my happy spaces and a happy place for many of us.

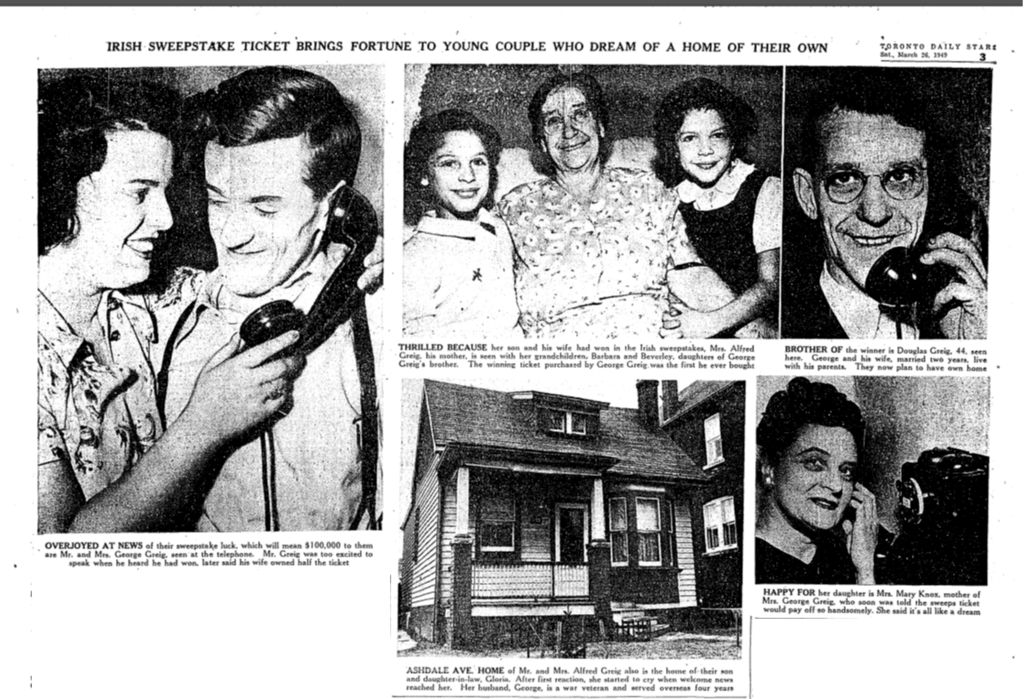

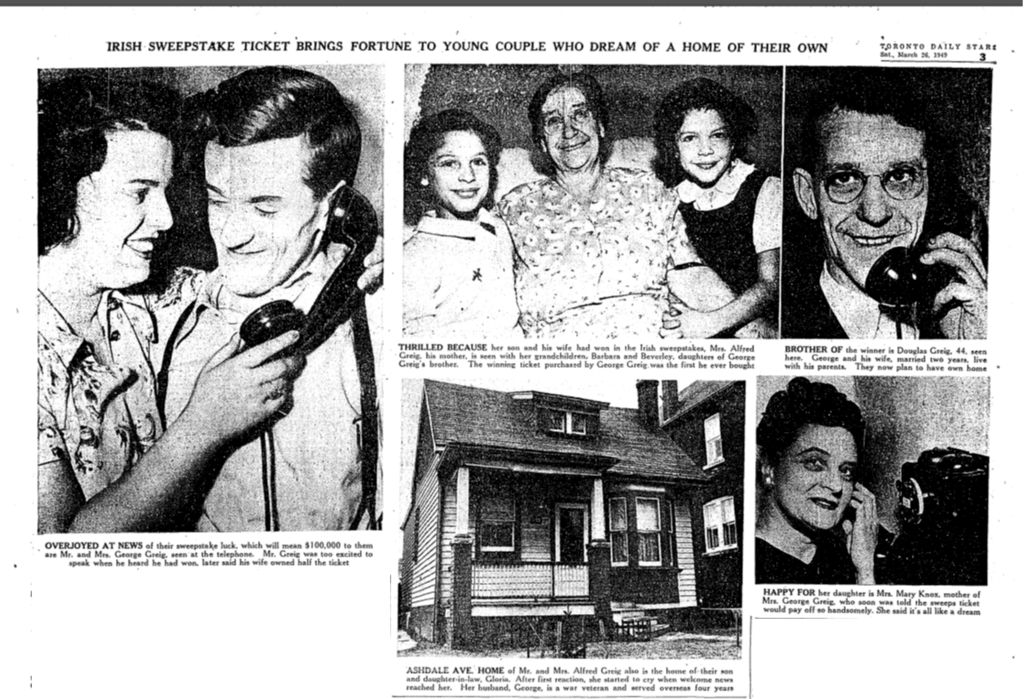

And it makes me happier thinking of hard-working people who had a stroke of luck. A family in my village also won the Irish Sweepstakes. My mother always said, “Money can’t make you happy, but it sure can make being miserable a whole lot easier.”

Our local merchants have made my life happier over and over again.

And even on the darkest days, there are rainbows in the sky and on the sidewalk. I took this photo on Woodfield Road.

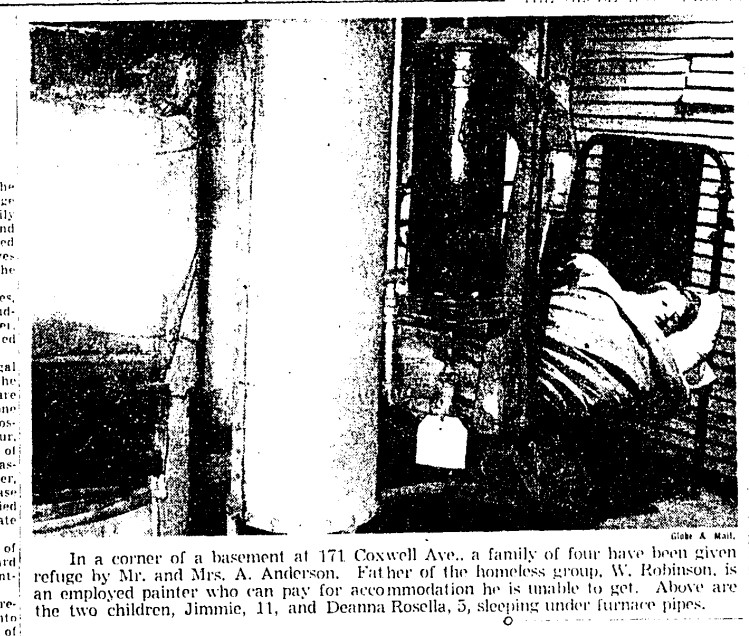

Articles and images from March 10th in the neighbourhood

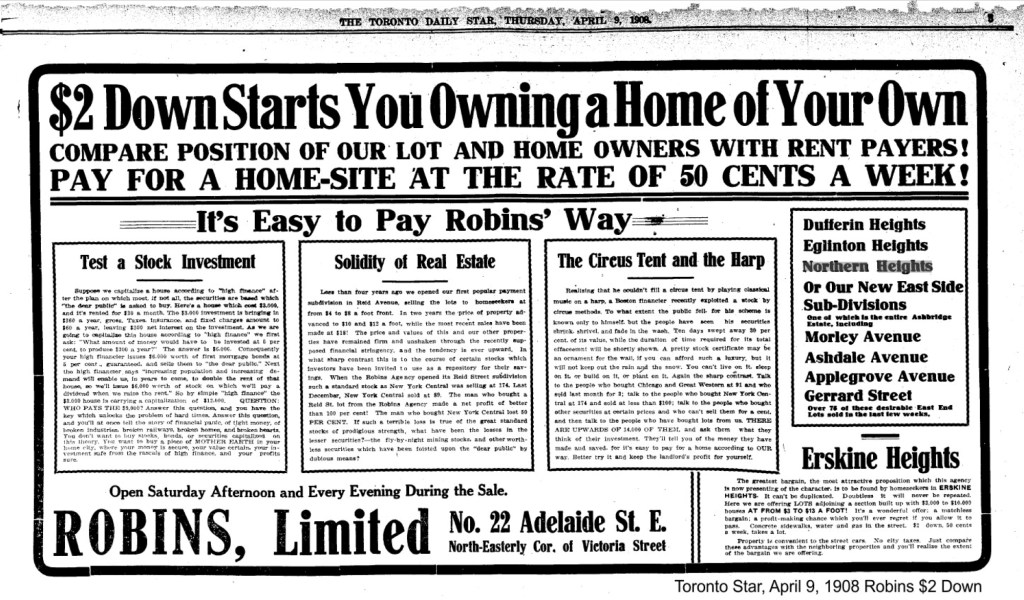

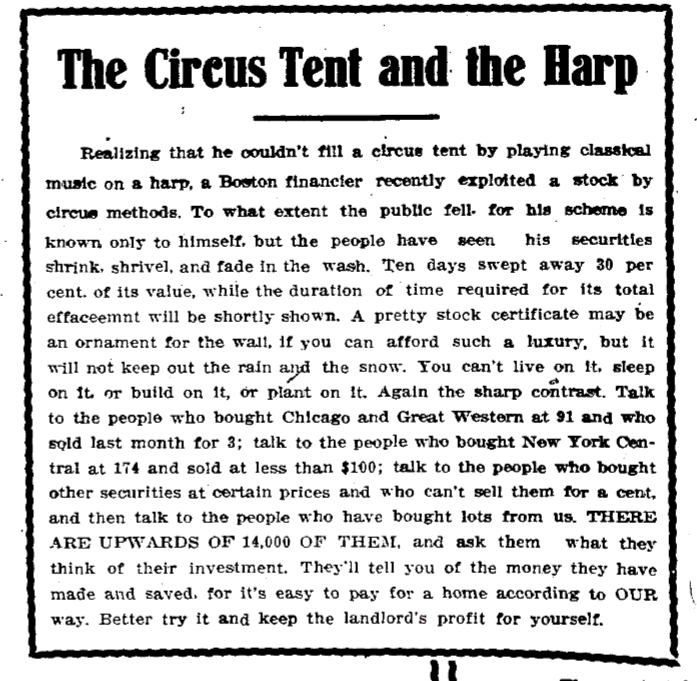

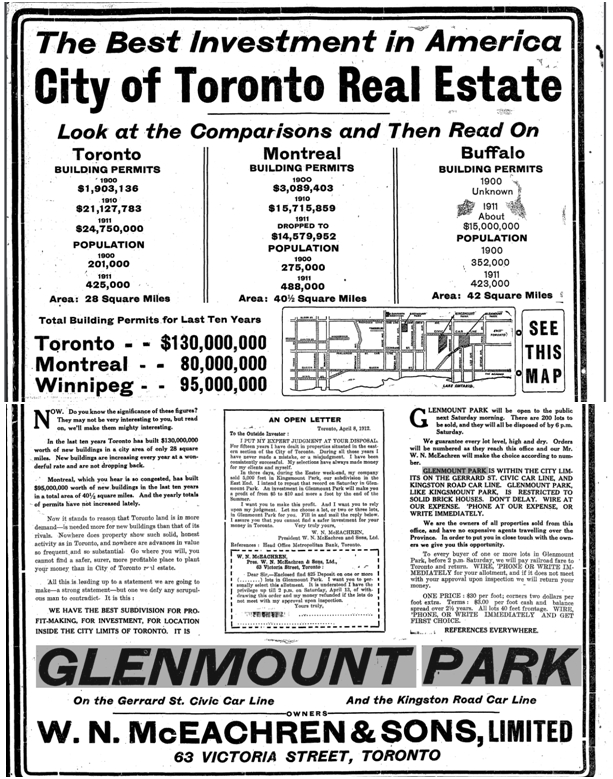

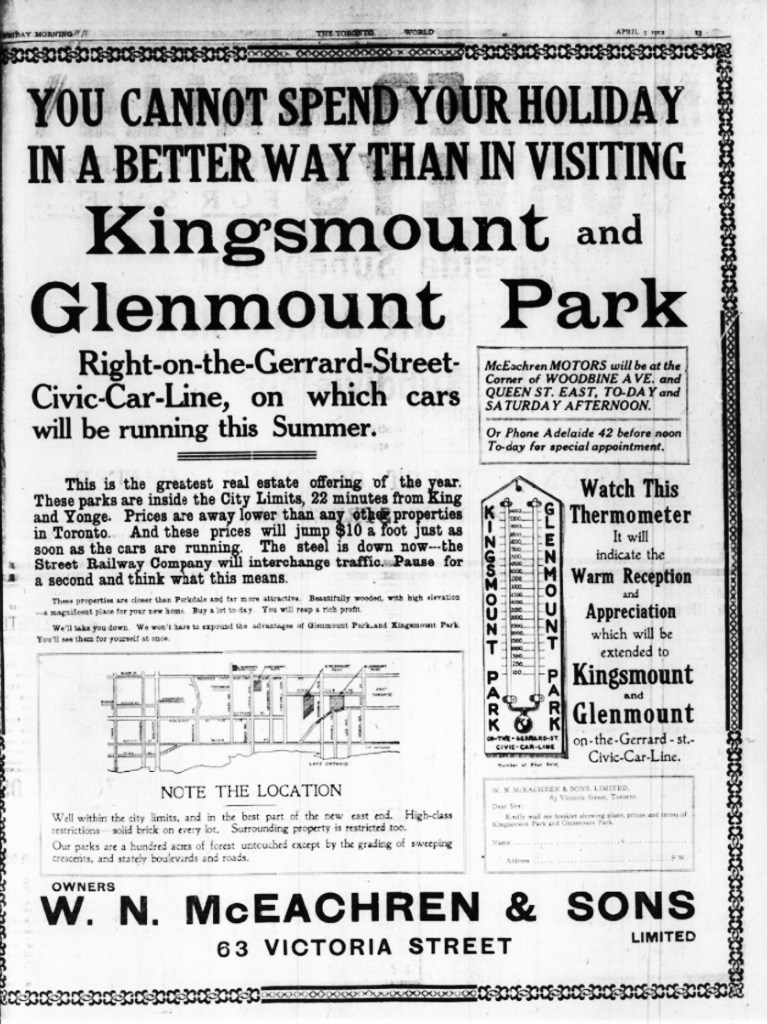

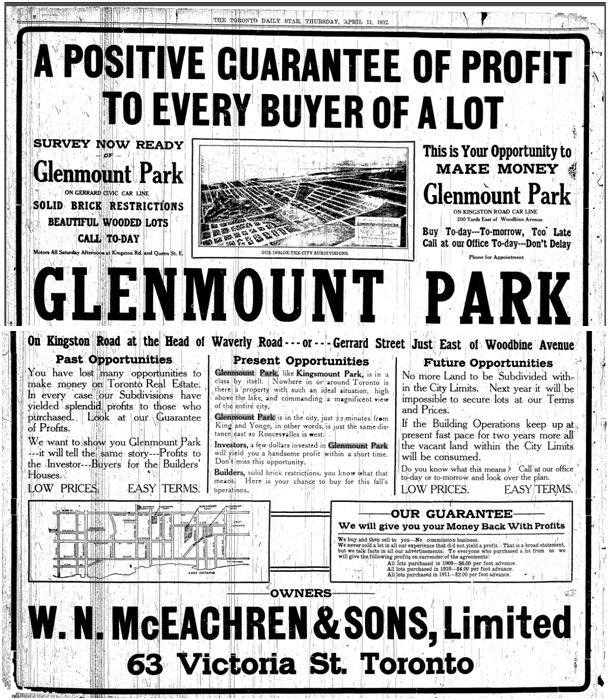

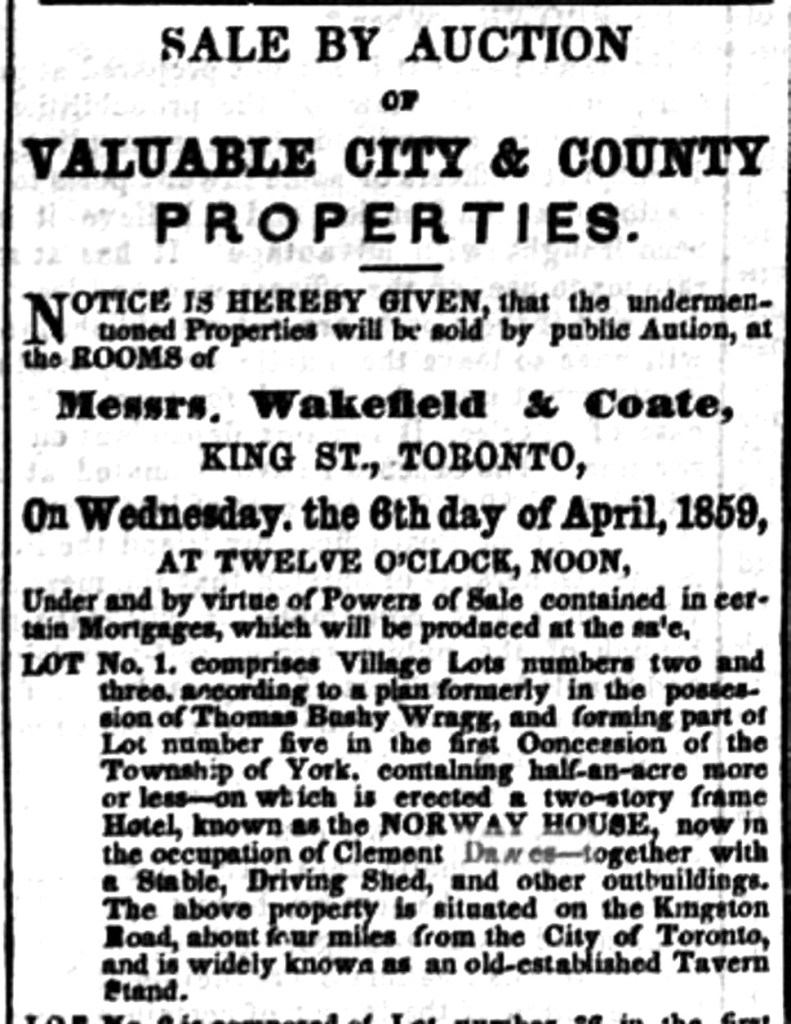

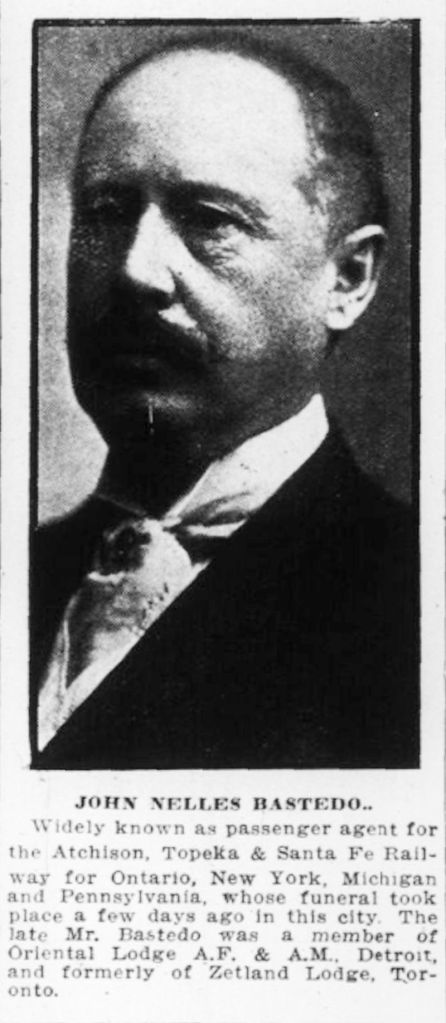

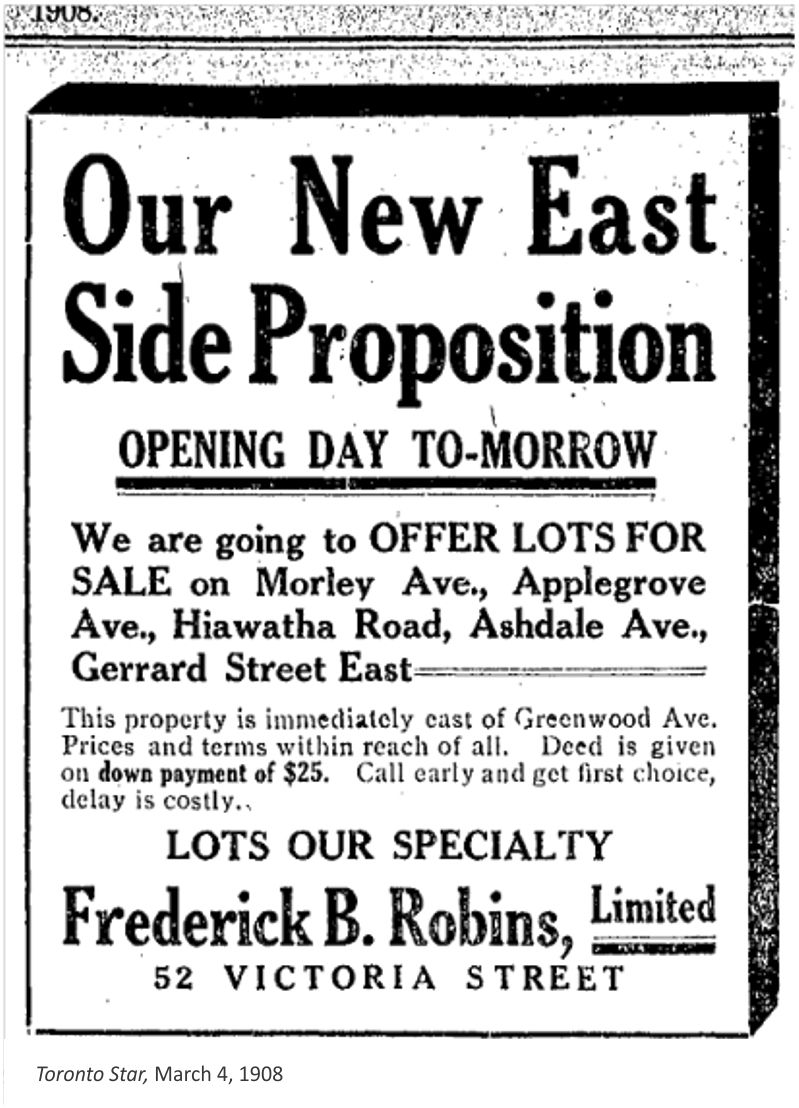

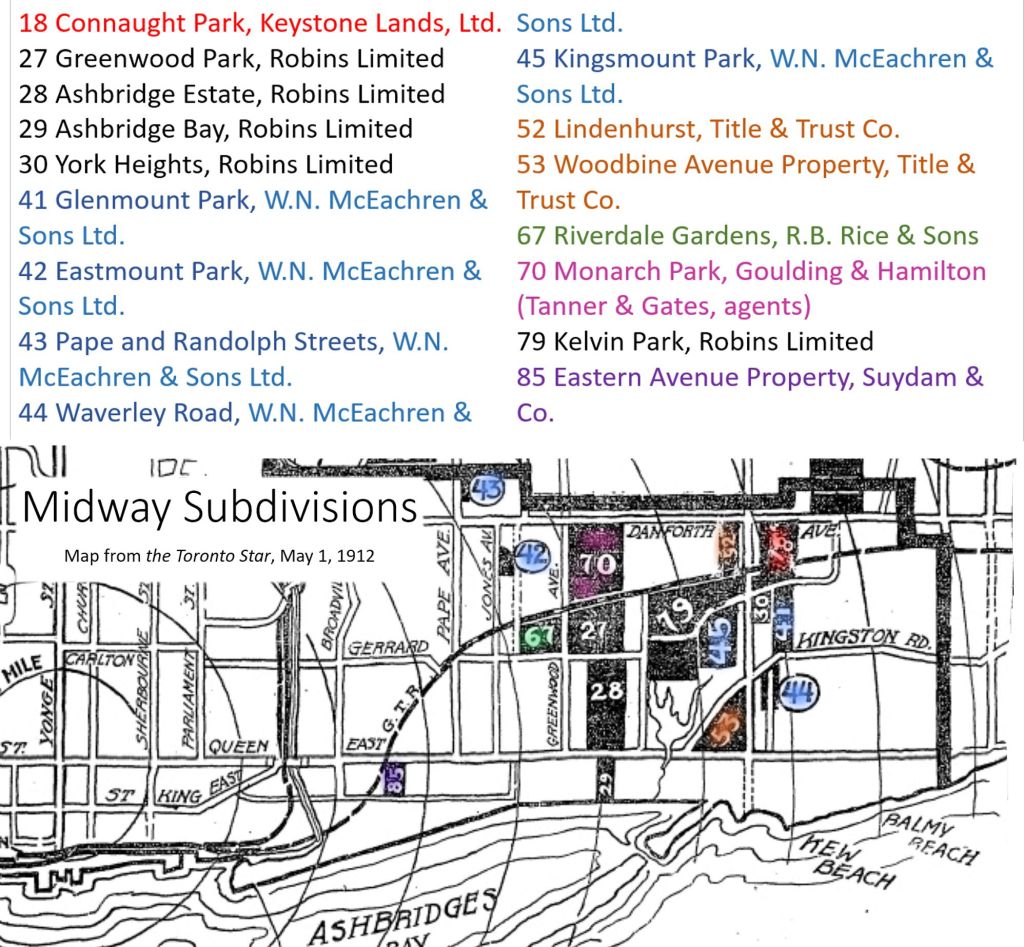

When the Ashbridges sold their farm west of the Toronto Golf Club grounds. F.B. Robins was their realtor. When Erie Realty Company sold lots on and just west of Coxwell Avenue, Frederick B. Robins was their realtor too. Henry Pellatt, F.B. Robins and their circle were known their free and easy approach to such things as insider trading, conflict of interest, and manipulating the markets.

While Robins and Pellat survived the Financial Panic of 1907, the crisis revealed the weaknesses of a largely unregulated financial sector.

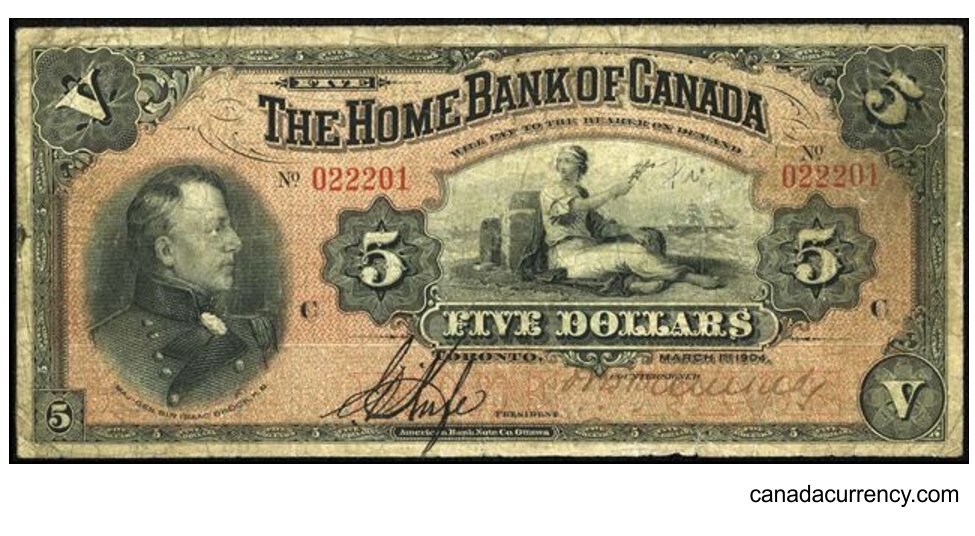

Five Canadian banks failed between 1905 and 1908. The failure, in January 1908, of the Sovereign Bank was the biggest, but not the last Canadian bank to fall. Bankers feared a domino effect. One of the banks Pellatt was involved with was the Home Bank of Canada, founded in 1903. It grew out of the Home Savings and Loan Company, created in 1854 to serve Toronto’s Catholics.

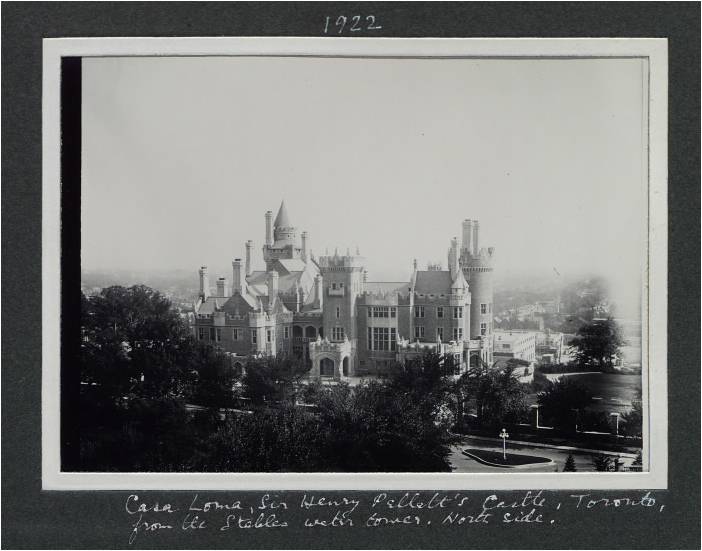

Pellatt with his castle, Casaloma, seemed to be Canadian royalty. But his wealth was built on offering risky investment opportunities to unsophisticated investors and using the savings of poor Irish Catholics through the Home Bank. Many investors in Pellatt’s enterprises were poorly equipped to evaluate risk and unable to afford losses. With this money, Henry Pellatt and Frederick B. Robins, both “land sharks”, bought up land on the fringes of Toronto and, in Pellatt’s own words, “nursed it along” until they could profit from the anticipated suburban growth.

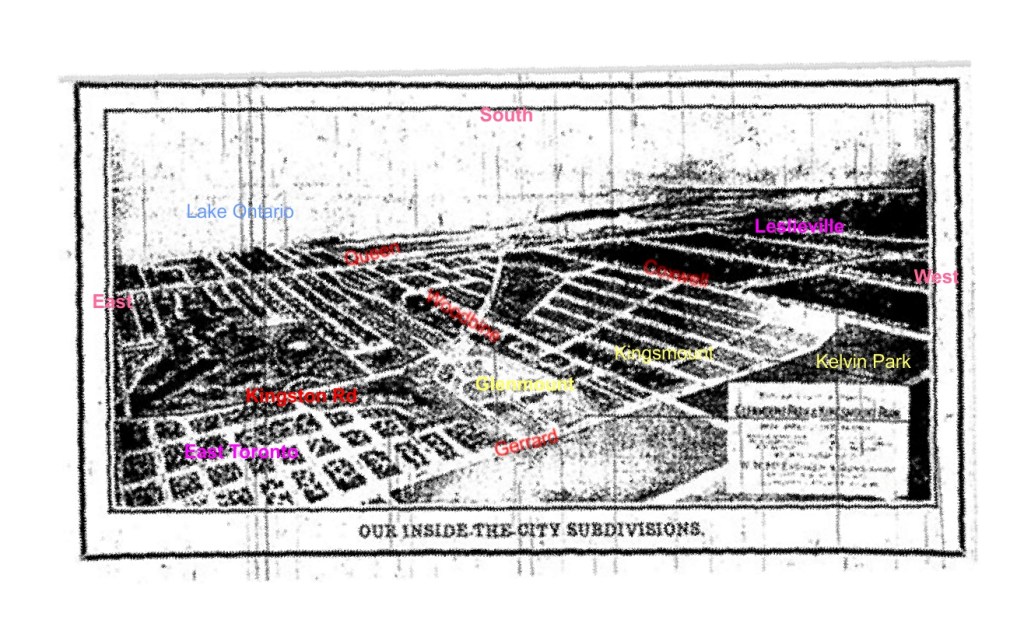

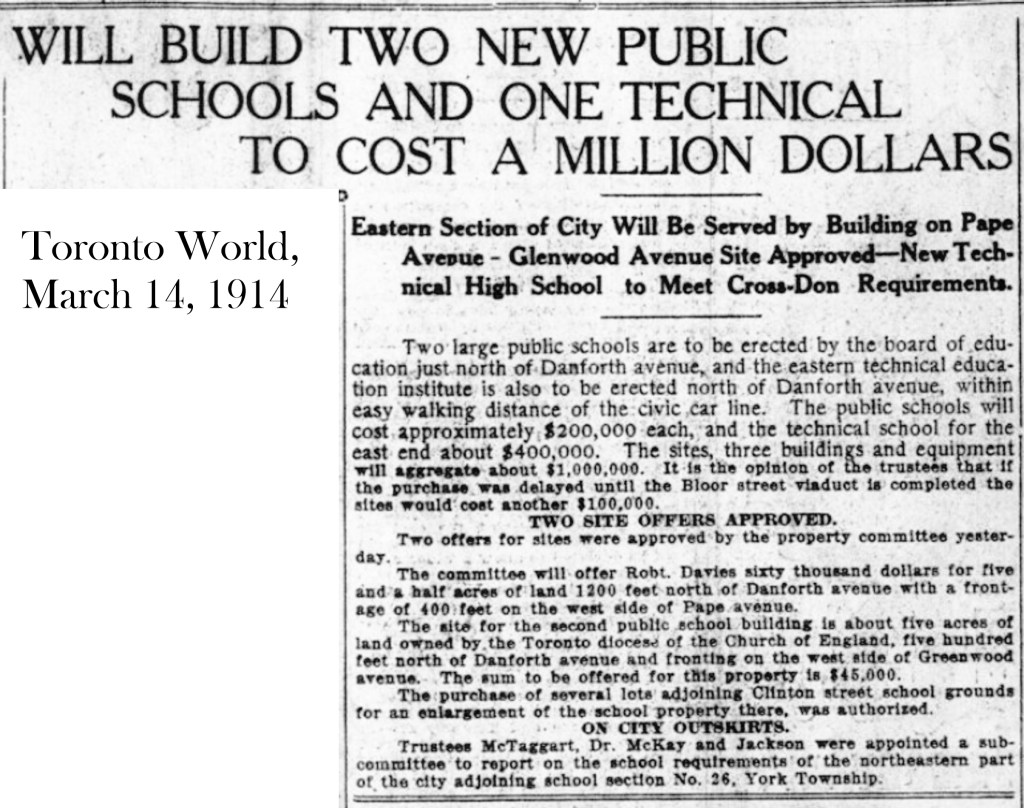

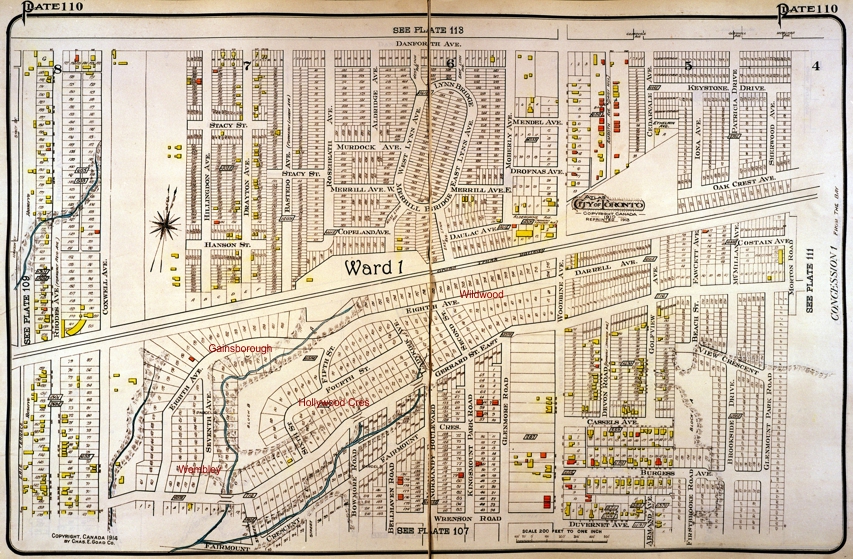

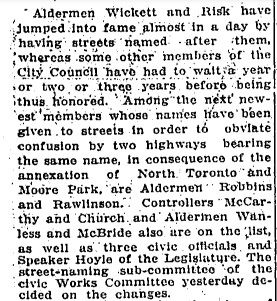

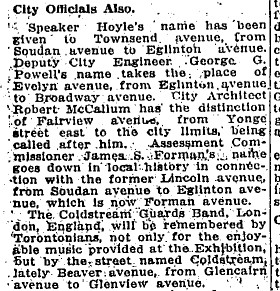

In 1909 the City of Toronto annexed the area south of the Danforth between Greenwood Avenue and the Town of East Toronto, allowing Toronto to expand eastward. Toronto City Estates incorporated in a partnership that would make Frederick Robins the real estate agent for almost all sales from Greenwood to Woodbine Avenues. Pellatt was a director of the Home Bank which lent millions to the Pellatt’s enterprises apparently without the knowledge of other directors.

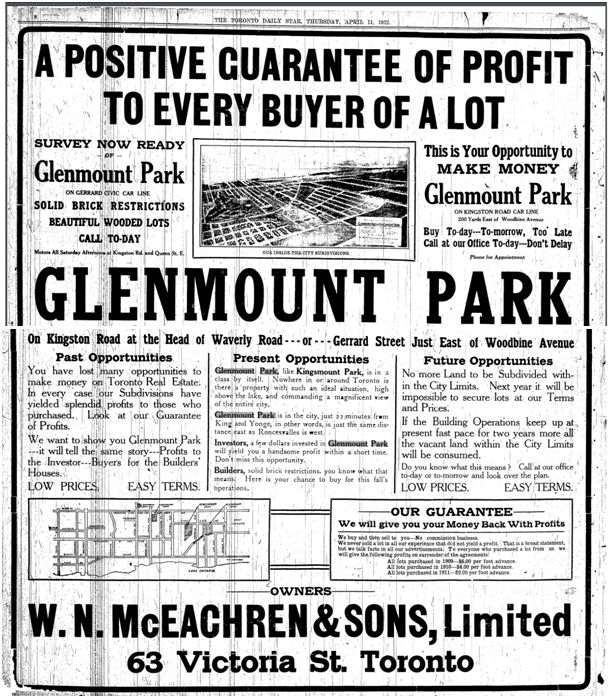

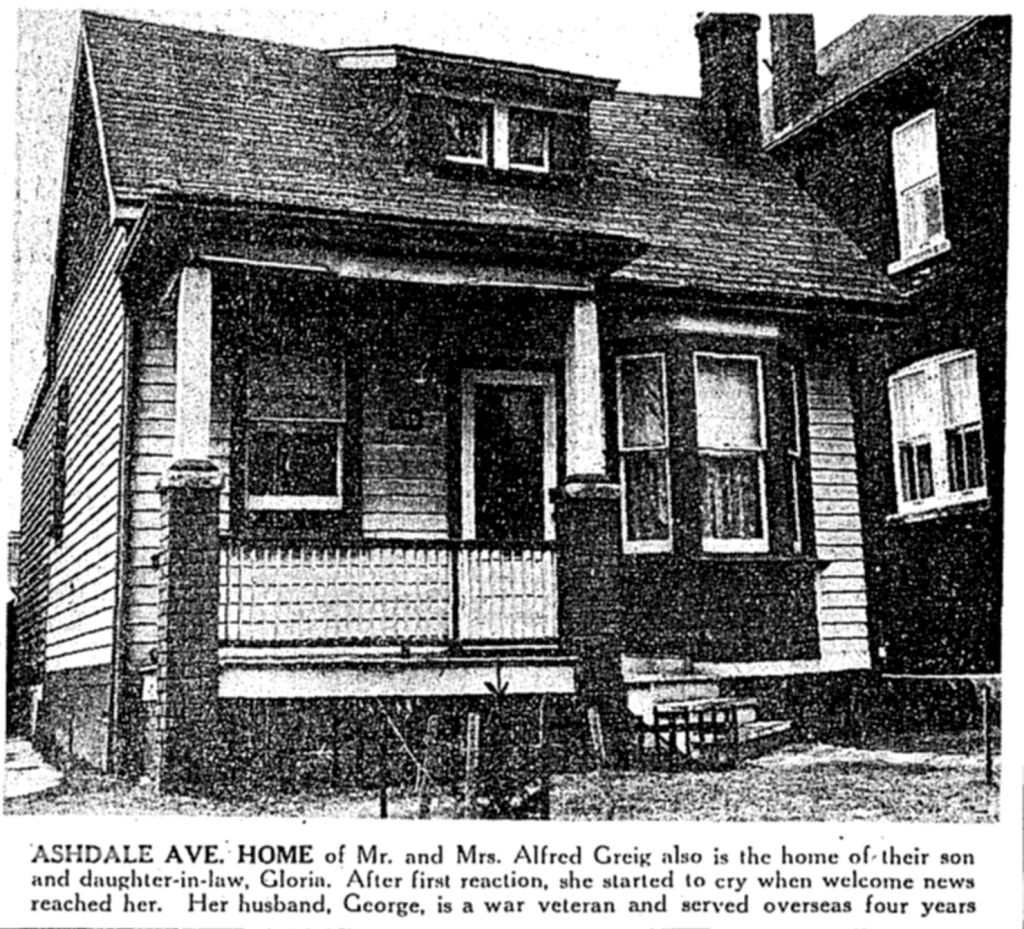

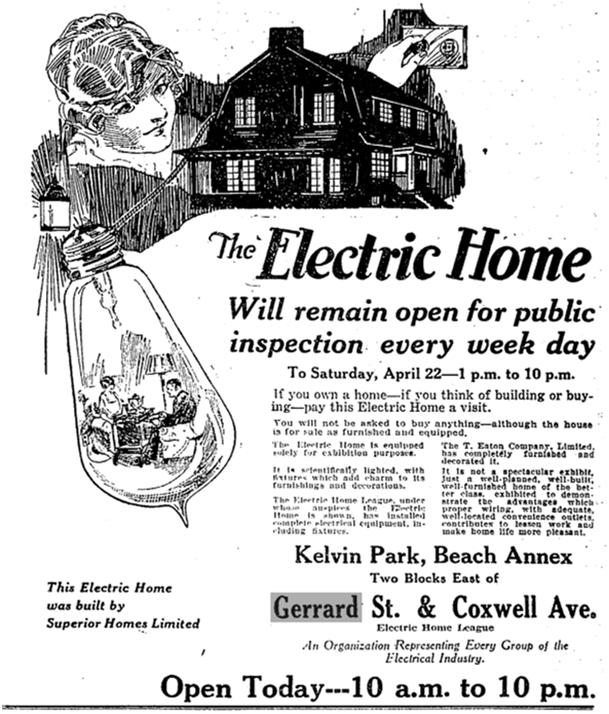

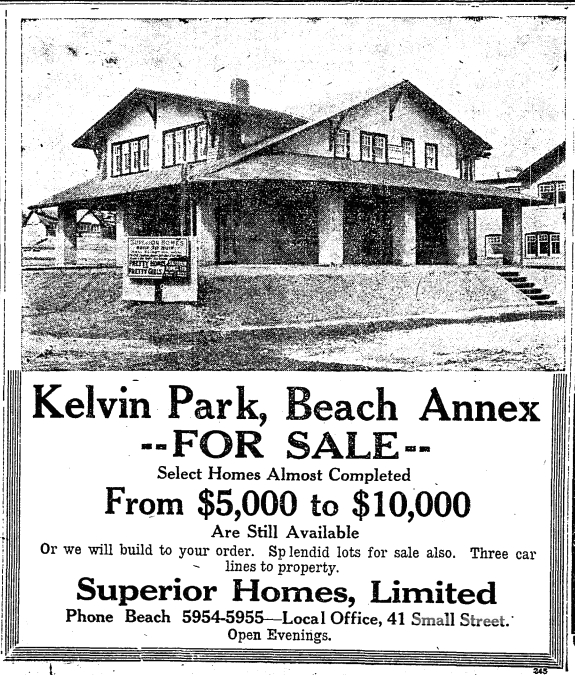

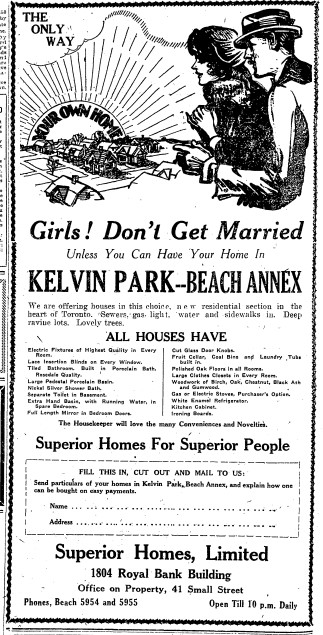

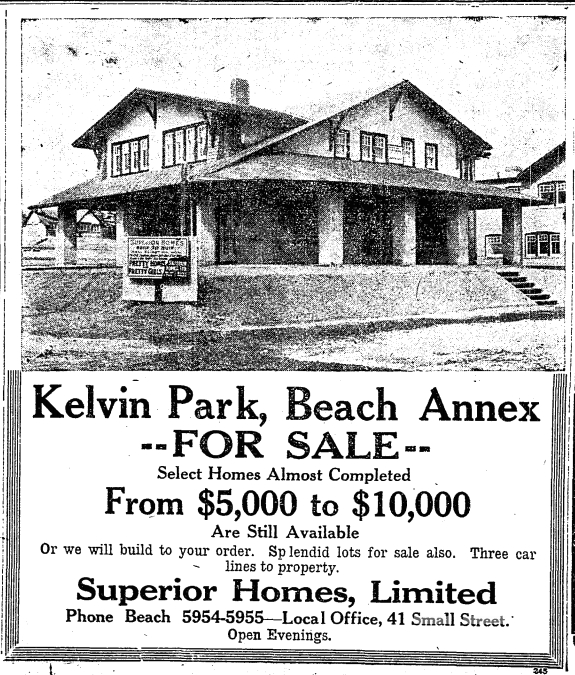

A genius in marketing, Pellatt renamed the Toronto City Estates subdivision on the Toronto Golf links. Its new name, Kelvin Park, suggested modernity and electricity. William Thomson, Lord Kelvin, died in 1907 the same year that Adam Beck brought Niagara’s electricity to Toronto. William Thomson was instrumental in the laying of the Atlantic Telegraph Company in 1856. This scientist, with his interest in the transmission of electricity. became a hero of the day and was knighted for his efforts, become Lord Kelvin. Kelvinator appliances (fridges, stoves, etc.) took their name from Lord Kelvin too.

Although favourable reports of Kelvin Park appeared in the British press, sales were slower than anticipated as another economic downturn preceded the First World War.

By 1914 the Home Bank was in deep trouble. Other bankers blamed Home Bank’s troubles on inefficient management and complained to the federal Minister of Finance. The Government of Canada refused to investigate the Home Bank, fearing this would cause the Bank to fail and destabilize credit vital to the war effort. The Bank promised to change and to reorganize its Board of Directors. However, the economy slumped after World War One. The Home Bank struggled on. Others went under went under.

In 1919 Standard Reliance Mortgage Corp., along with its subsidiaries was insolvent. F.B. Robins was the major stockholder in Dovercourt Land Company, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Standard Reliance. Yet Frederick B. Robins managed to survive and continue dealing in real estate.

In 1923 a housing boom started to fill the area with homes. But it was too late for Henry Pellatt. On August 17, 1923, the Home Bank suspended operations. The misstatements on the financial reports and other deceptive practices added up to a disaster for depositors. The Bank over-valued its collateral which was mostly real estate, and, on this shaky basis, loaned money. Home Bank’s liabilities far exceeded its assets. There was little actual cash in the Bank’s own account. Nearly $2 million dollars was loaned by the Home Bank to Toronto City Estates. Sir Henry Pellatt was both the President of Toronto City Estates, and a director of the Home Bank. Loans were secured by the Bank’s and its subsidiaries worthless stocks, as well as overvalued properties and mortgages.

Sir Henry Pellatt was a broken man. His wife died, he lost his castle, and he ended his days living with his former chauffeur in a small Etobicoke home. F.B. Robins emerged unscathed and went on to be appointed as a diplomat representing Canada abroad.

Providential Investment Company and Superior Homes took over the sale of Kelvin Park. Sales skyrocketed and houses went up to line the streets where they still stand today. Two show homes graced Kelvin Park: a classic Arts and Crafts bungalow and a hip-roofed home, known as “the Electric House”, used to showcase electric lighting, heating, and appliances. Sales of electric appliances and homes skyrocketed. Although the name Kelvin Park has been forgotten, the houses built from 1923 to 1929 still line the streets that lie where the greens and fairways of the old Toronto Golf Club were.