CNR Tempo train lies scattered across the railway right-of-way year Woodbine Racetrack after running through an open switch April 20, 1969 by Bob Olsen, Toronto Star

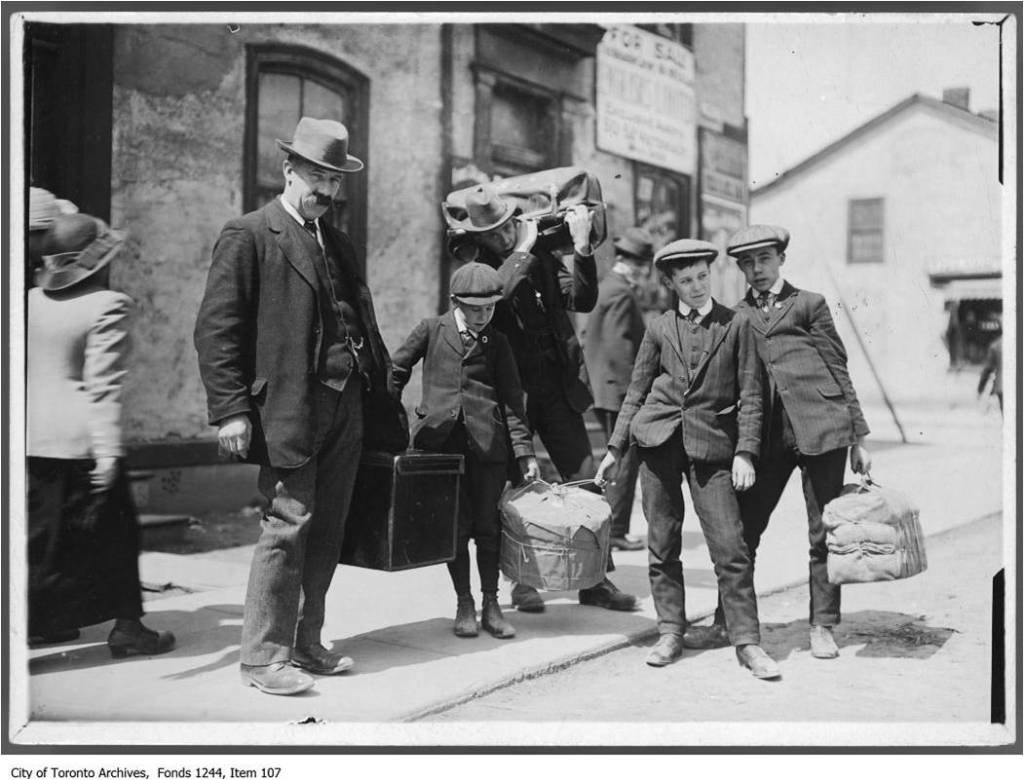

Shacktowns were full of young couples, new immigrants from Britain. In many cases they were very poor. Their ship passage to Canada was subsidized by “the British Bonus”.

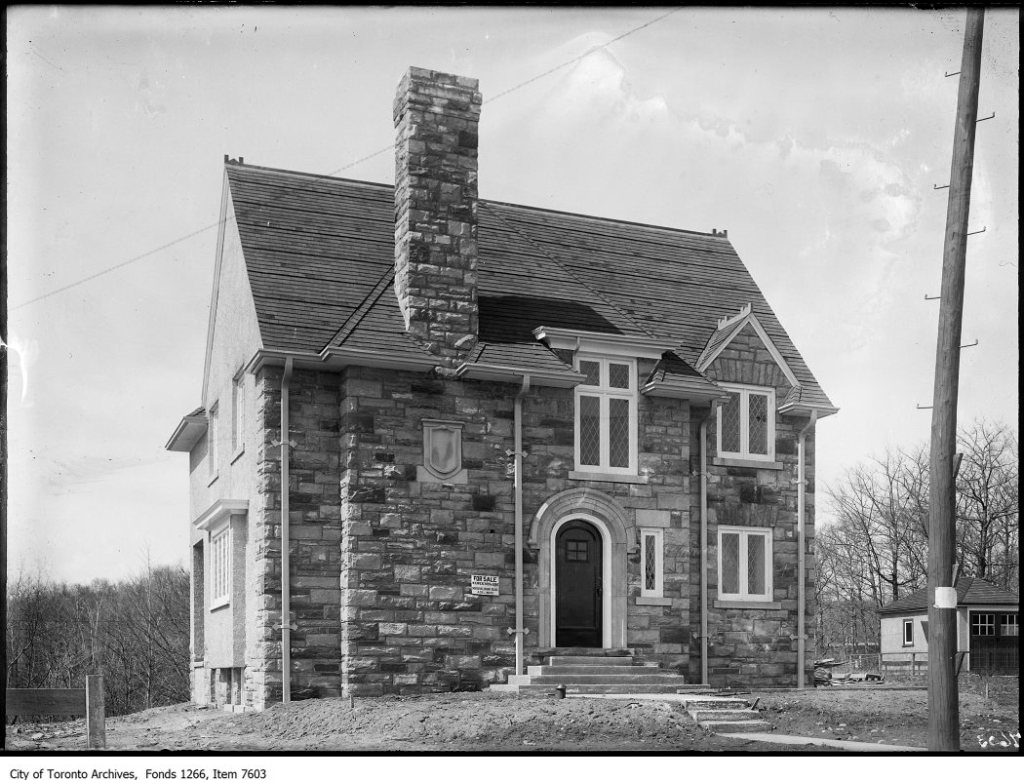

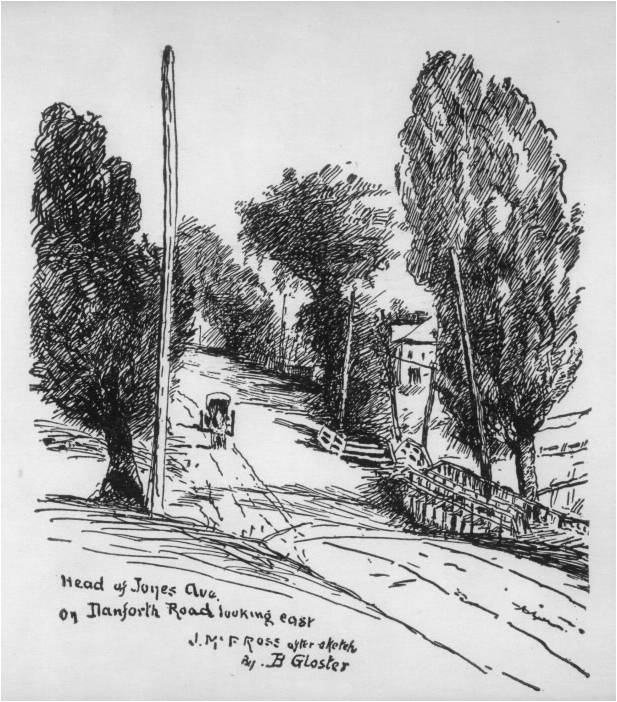

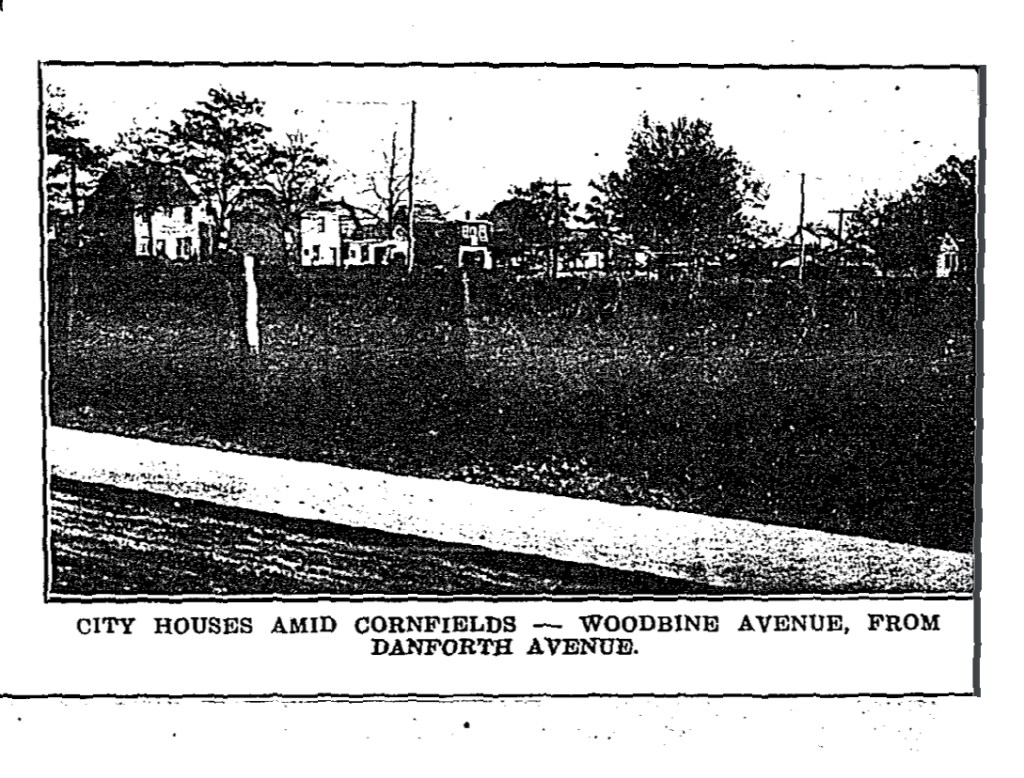

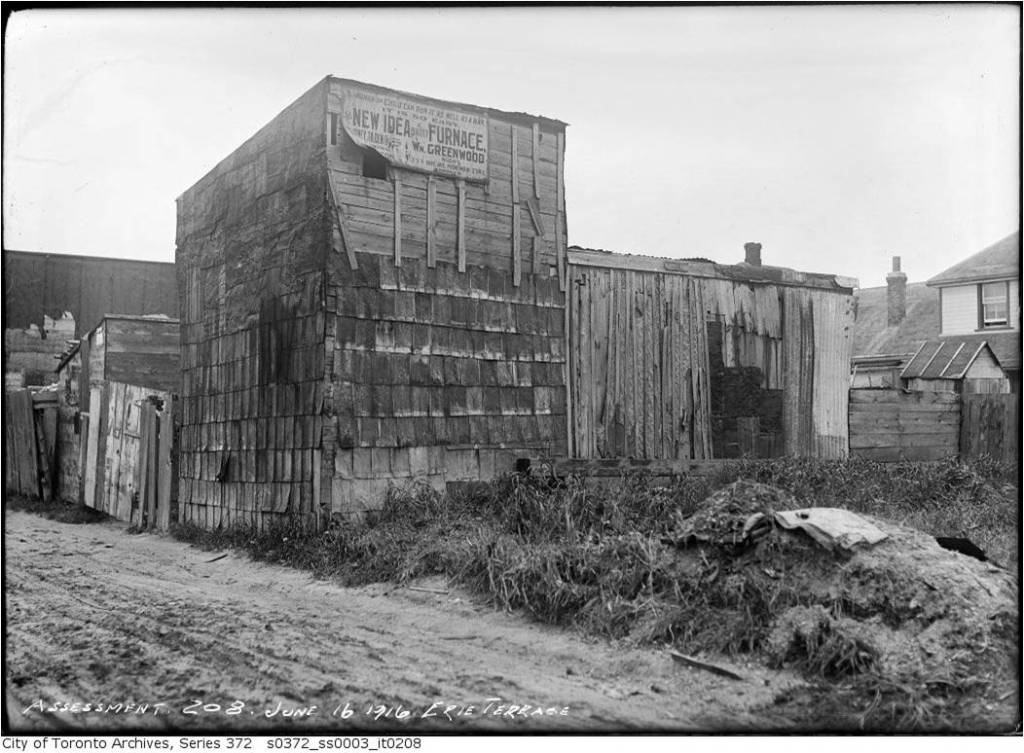

York Township, just outside Toronto provided cheap building lots where they could build their own homes from whatever they could scavenge or scrouge:

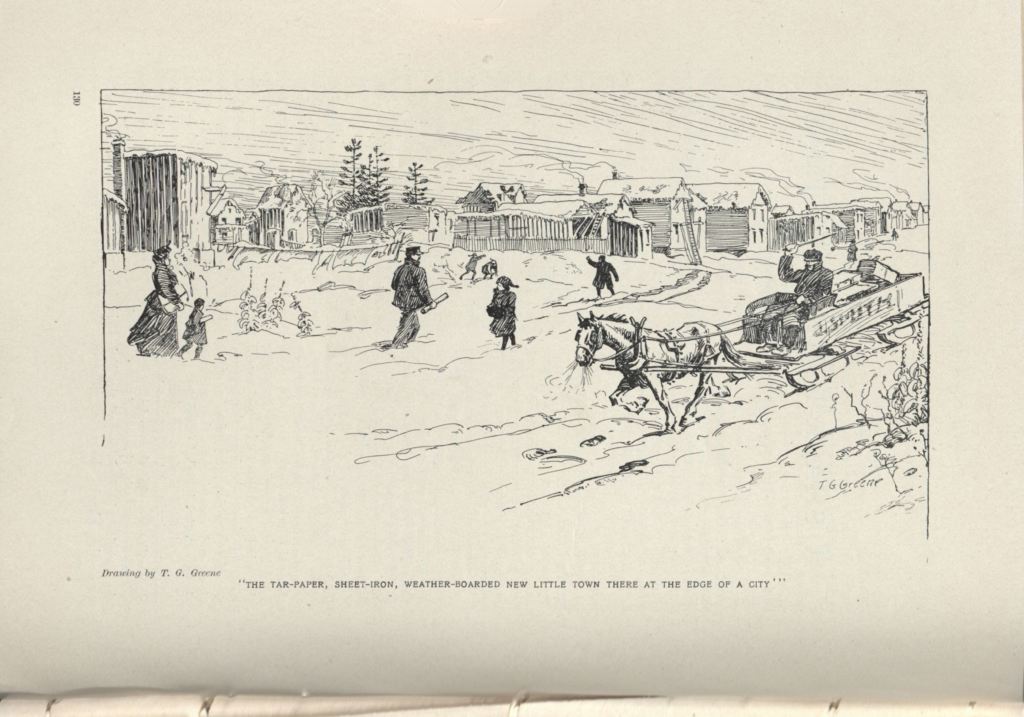

Thanksgiving Day was the busiest of the year in Shacktown…the outer fringe of the east and the northwest district.

There was one last holiday before winter to get work together to put up each other’s homes.

Brick, roughcast, clapboard, plain board, cement blocks, shingles, tar-paper fronts and roofs, glorified packing cases, are all to be seen in the streets of Shacktown. The work seems to be done largely on holidays, on the “bee” principle. A group of bricklayers can be seen here and there rushing up a brick front, while around frame structures that rise while you wait carpenters are swarming—quite properly, if it is a bee.

…The settlement is the newly-arrived Britishers’ answer to the demand for $18 and $10 a month for working-class houses. With a couple of thousand feet of lumber, two or three lengths of stove-pipe and the help of his chums on such a holiday as yesterday the shacker becomes his own landlord. (Globe, Nov. 1, 1907)

Shacktown was the working class immigrants’ collective solution to a housing shortage. The welfare state as we know it today simply did not exist. There was virtually no public housing except The Poor House.

The Shackers had high hopes for themselves, their children, their neighbours and their tarpaper shack towns, but an economic downturn and an extremely cold winter hit like a hammer in December 1907.

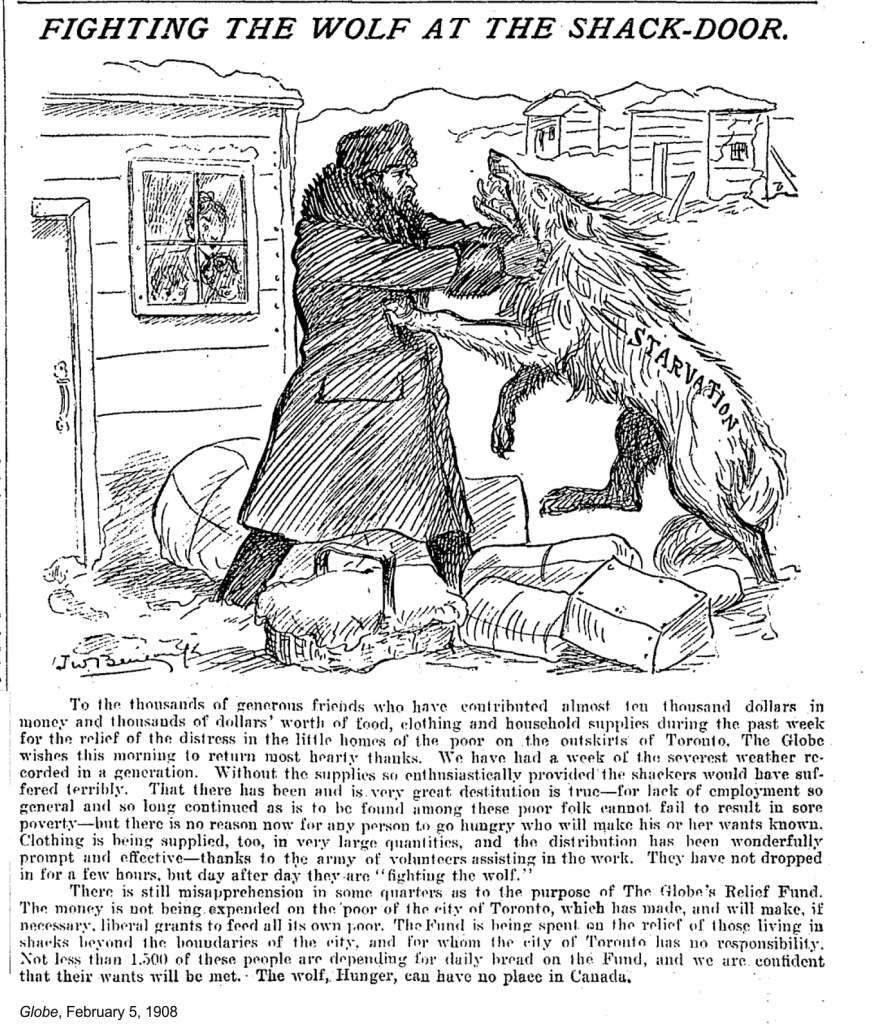

Unemployed, without food, fuel and proper clothes for the first hard Canadian winter, the British immigrants began to suffer intensely. Shacktown had no government, no charities, men out of work, women worn out. Globe reporters found families without any fuel, with nothing it, with frost bitten, and members critically ill without doctor’s care or medicine, or even blankets. Some people were still in tents.

The sound of little children crying was yet in the wind that whimpers and blow over the land of tar-paper homes when The Globe reporter visited it last night. (Globe, Feb. 1, 1908)

The Globe launched the Shacktown Relief Fund on January 27, 1908, and immediately money poured in, as well as clothing, food and fuel. However, Shacktown that winter shocked even experienced social workers (known as “relief workers” then). It changed how they thought about people in need.

Women without proper winter clothes, garbed in a grab bag of materials, plowed through high snow banks to the distribution depots where they waited in lines for food, fuel or clothing. People were quietly keeping “the stiff upper lip” the British were known for and suffering intensely behind their tarpaper walls.

A twelve-year old girl looked after her six younger brothers and sisters alone. The mother had died in October, 1907, and the Dad spent all their savings on his wife’s funeral. Then he was laid off and so was left with nothing to draw on during that awful winter. Neighbours pitched in to help the twelve-year old who was responsible for making the fire in the stove and keeping it going, cooking the meals, washing and clothing the other children. For two weeks the family subsisted on liver and potatoes and nothing else. Tthen the father became ill and the girl called a doctor in. He diagnosed a case of bronchitis, serious in those days before antibiotics. As the doctor tended the sick man, his six younger children crowded on another bed across the room, huddled behind their older sister. Chilled to the bone, the doctor asked the girl to put some coal on the fire:

“Please, could you let us ‘have a bit o’coal?”

“No sir,” replied the little head of the house. “That’s the last of it. I picked it up along the track just so long as I could, sir. I used to get quite a bit, but I ‘urt me foot and m’shoes wore out, so I couldn’t go any more, sir.

Like many other children, she had been scavenging along the railway tracks where bits of coal fell off the trains. The fireman shovelled coal into the furnace on the locomotive, creating the stem that powered the engine. Sometimes unburned chunks flew off, but half burned pieces called “clinkers” also flew through the air. The first children on the scene when a train passed were the most likely to get some free fuel. This created a rush of boys and girls along the tracks through Shacktown, a dangerous situation. A number of children met gruesome deaths, mangled by trains.

The doctor questioned the kids and they told him they had been living on potatoes alone for two days. When the spuds ran out, they were reduced to boiling water in an old tin that had held soup. This thin broth was all they’d had for several days. The day of the doctor’s visit, the children had absolutely nothing to eat. Like the proverbial old-fashioned country doctor, the physician “stepped up to the plate” and got groceries and fuel for the family out of his own pocket. Not only that, but he helped the father find temporary work. The doctor even paid a woman from the neighbourhood to look after the children, including the twelve-year old girl.

Robert Gay, the minister of St. Monica’s Church (where the Toronto Public Library’s Gerrard-Ashdale Branch is today) described his experience:

“I visited a home yesterday and found a man with his wife and eight children, living on what the oldest girl, aged eighteen years, could earn. The husband was out of work, as was also the oldest boy, a lad of sixteen years. I had great difficulty in eliciting any information from the family. I found them lacking bed clothing, food and fuel. So cold had the house been that there had been ice on the walls of the bedrooms. With the assistance of a neighbor we moved the solitary stove, so that its heat would be evenly distributed. Stovepipes were bought and blankets and food supplied. The coal was delivered later.

By mid February, 1908, Shacktown or “the Tar Paper Region” was beginning to feel the impact of the Shacktown Relief Fund. Contributions of both goods and cash were flowing in. The crisis was over.

By 1912, people were nostalgic for that magical summer of 1907, “There is more fun in Shacktown than in your big city.”

A couple married without any money and spent their first nights together in a rough honeymoon suite: “Their first shelter was a few boards leaned up against a fence, and they snuggled under.

They cooked amazing dinners outdoors. They sat under the moon for amazing nights. Sometimes they didn’t know where their breakfasts were coming from, but nevertheless they slept well.”

But employment picked up and in a few years they had finished a sturdy bungalow but life was not as exciting as that first summer under the stars in Shacktown. People mourned that “The good old days of Shacktown are slipping away.” (Toronto Star, April 12, 1913)